What do worm blobs and insect pee have to do with human health? We talked to Saad Bhamla, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) in Atlanta, to find out.

Q: What did your path to becoming a scientist look like?

A: I grew up in Dubai and did my undergraduate work in India, which is where I was first introduced to science. The science faculty members seemed to be having so much fun and would say things like “for the love of science,” but I couldn’t figure out what joy they were getting until I got a taste of it myself—then I was hooked. I like the idea that you can create a legacy doing science because someone can come along 100 years later and build on your work.

After undergrad, I went to Stanford University and earned my Ph.D. in the lab of Gerald Fuller, Ph.D., and then stayed at Stanford for postdoctoral work (postdoc) in the lab of Manu Prakash, Ph.D. In 2017, I joined the faculty at Georgia Tech. On paper, I’m a chemical engineer, but I describe myself as more of a biophysicist.

Q: What are you researching in your lab?

A: The work in my lab falls into two thematic focuses under the umbrella of what I describe as curiosity-driven science. The first focus is on the physics of living systems and the second is frugal science—which may seem very different from one another, but they both require us to be curious but also to be comfortable with open-ended, hard problems. We don’t always know what questions we’re going to answer or what device we’re going to invent.

We study all different scales of life, from proteins and cells to collectives of cells and organisms, using biophysics, physics, robotics, and mathematics. I often get questions about why we study things like how insects pee or how worms blob or why single cells contract, but we do this basic, curiosity-driven science with the hope that it will enable others to see something to build upon and eventually improve lives. Without basic science, we can miss the forest for the trees if we just focus on specific applications. We need basic science to be able to innovate in the applied sciences.

Frugal science, the second focus of the lab, is where we actually do something tangibly useful and build very low-cost tools, like a paper centrifuge inspired by a whirligig toy or a hearing aid that costs a dollar to make. I’m realizing that just like any other aspect of science, you can teach people to do frugal science. I want to democratize not just the tools we create but the knowledge we use to identify a problem and come up with clear and clever solutions. We need many more innovative people who realize they can do things on a shoestring budget.

Q: Your lab uses a lot of nontraditional research organisms. Can you talk a little more about that?

A: I think every organism can be a research organism. We can’t ask all questions in mice or fruit flies, so we need to explore other organisms. Our lab is studying (or has in the past) how:

- Flamingoes filter their food

- Sled dogs work together as a unit

- Single cells learn without neurons

- Worm blobs tangle and untangle

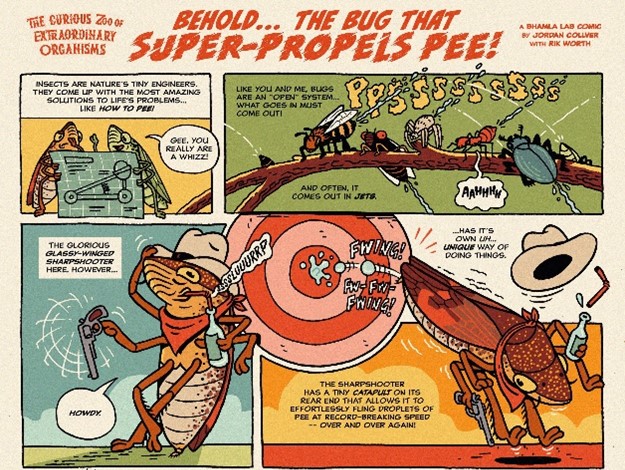

- Insects like sharpshooters and cicadas pee

- Slingshot spiders build 3D webs to hunt at night

- Mudskippers blink

- Springtails (the most abundant arthropod in soil) leap

- Termites in the Amazon shoot out “liquid lassos” to trap ants

- Water striders live on moving water

We want to understand the physics behind how these organisms do what they do so that we can harness it for something that can ultimately improve human health. For example, rhagovelia, a type of water strider, has two genes that control a fan on its legs, and it literally flies on the surface of water. We’ve developed robots with that small fan that can “walk” on fast, turbulent water.

Q: What inspired you to venture into frugal science?

A: As I was finishing my Ph.D., I was trying to figure out what I’d done to reach one of my goals, which was to use my engineering and science knowledge to improve the lives of people. Yes, we’d built a device that would improve some contact lenses and help some people with dry eyes, but I felt like I could do so much more than that. Around that time, scientists at serious research institutes were thinking frugally, thinking about accessibility for not just you and me, but for billions of people—like planetary scale. One of them was Dr. Prakash, and he’d just invented a $1 paper microscope. That’s when the “aha” moment came, and I knew that’s what I wanted to do. During my postdoc, I developed the cousin to the paper microscope: a paper centrifuge.

Q: What are your goals for your career?

A: I want to keep having fun doing science, and I want to help inspire others, regardless of their background, to invent, create, and ask questions. I think I’m going to be so happy looking back on my life that I’ll have trained a small group of the right people who typically wouldn’t have realized their potential to be a scientist or an entrepreneur. That’s the secret to education—my $1 hearing aids may improve some lives, but I think it’ll be the team member I trained that will go on to do something that will have much more impact than any device I make.

Anybody can innovate and come up with a good idea, and as an advisor, my job is to help execute my students’ good ideas. For example, a high school student in my lab, Gaurav Byagathvalli, came up with the idea to use a barbecue lighter to replace an expensive piece of equipment that’s used to genetically modify cells called an electroporator. We saw the potential for a DNA and RNA vaccine delivery system, and we took the idea to another professor here at Georgia Tech, Mark Prausnitz, Ph.D., who works with microneedles. Together we were able to develop a barbeque lighter-based microneedle drug delivery system. Guarav finished high school and then undergrad, and he’s now the CEO and co-founder of a startup company based on the technology, showing the power of frugal tools all the way from an idea on a white board to translation into a commercial product. And even more than that, a high school student creating something and now leading a company!

Q: What advice would you give someone starting a career in science?

A: Be the best version of yourself. You don’t have to be a version of your advisor or your parent. Find what gets you going and follow that. Sometimes it’s the big, hard problems or sometimes it’s the whimsical problems, but figure out what excites you because then you’ll be the most creative. I encourage my students to be a little bit more promiscuous in their thinking because you never know where unconventional ideas will come from.

And find ways to engage with your audience and make your science accessible. As scientists, we think publishing a paper will lead to everyone reading it and that tomorrow things in the field will change. But in reality, that doesn’t happen. In our lab, we’ve started creating comics to tell the story of our work in a way that students can relate to. And we’re translating them into lots of different languages. How are we going to attract students to think about science if what we’re putting out there isn’t accessible and attractive to them?

Dr. Bhamla’s work is supported by the NIGMS Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award program through grant R35GM142588.