Dave Cummings

Field: Environmental microbiology

Works at: Point Loma Nazarene University, San Diego, Calif.

Hobbies: Hiking, backpacking, fly-fishing

Dream home: One that doesn’t need a lot of work

Credit: Marcus Emerson, PLNU

In college, as a pre-med student majoring in biology and chemistry, Dave Cummings grew frustrated with the traditional “cookbook” approach to doing labs in his science classes. Turned off by having to follow step-by-step lab procedures that had little to do with scientific discovery, Cummings changed his major to English literature. Studying literature, he says, “helped me find myself” and taught him to think critically.

Ultimately, Cummings says, “I came to realize that it wasn’t the practice of medicine that got me excited, but the science behind it all.” He decided to pursue a graduate degree in biology and—after “knocking on a lot of doors”—was accepted at the University of Idaho, where he earned his master’s and doctoral degrees and discovered his passion for microbiology.

Today, Cummings applies his critical thinking skills to his work as professor of biology back at his alma mater, Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU), a small university focused on undergraduate education. There he studies the role of urban storm water in spreading genes for antibiotic resistance in natural environments, and pursues his enthusiasm for training the next generation of scientists. He enlists his students in his research, giving them what he calls “real, live, on-the-ground” research experience that relatively few undergraduate students at larger universities receive.

Cummings’ Findings

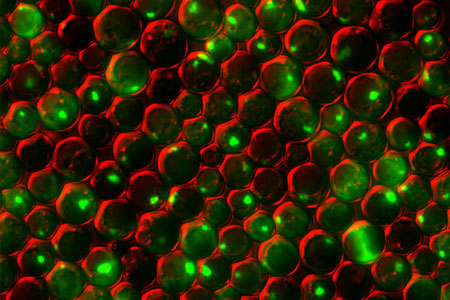

Antibiotic resistance, which can transform once-tractable bacterial infections into diseases that are difficult or impossible to treat, is a major public health challenge of the 21st century. The most common way that bacteria become drug resistant is by acquiring genes that confer antibiotic resistance from other bacteria. Often, such drug resistance genes are found on small, circular pieces of DNA called plasmids that are readily passed from one species of bacteria to another.

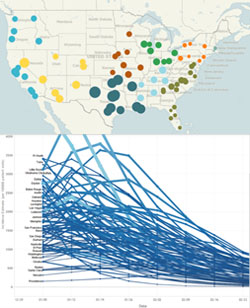

Urban wetlands provide ideal conditions for bacteria to mingle, swap genes and spread antibiotic resistance, notes Cummings. He focuses on the wetlands around San Diego, which act as a giant mixing bowl for storm runoff, human sewage, animal waste, naturally occurring plant and soil microorganisms, and plasmids indigenous to the wetlands.

Cummings and his students examine sediment samples from these wetlands in search of plasmids that carry resistance genes. They’ve found that during winter rains, the San Diego wetlands receive runoff containing antibiotic-resistant bacteria and plasmids, which can persist at low, but detectable, levels into the dry summer months.

“We know that urban storm water carries with it a lot of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and along with that the DNA instructions [or genes] that code for the resistance,” says Cummings. “We have solid evidence of genes encoding resistance to clinically important antibiotics washing … into coastal wetlands in San Diego.”

“We’re trying to understand the scope of the problem, and ultimately what threat that poses to human health,” he says. His concern is that the drug-defying bacterial genes will accumulate in the wetlands, and then “[find] their way back to us, where they will augment and amplify the problem of resistance.”

Precisely how resistance genes might move from the environment into people is not yet known. One way this could occur is through direct contact with contaminated water or sediment by anglers, swimmers, surfers and other recreational users. Fish, birds and insects could also transmit resistance genes from contaminated wetlands to humans.

“There is good evidence elsewhere that birds are important vectors of drug-resistant pathogens, and this is my favorite possibility,” says Cummings. “Hopefully someday we can test that hypothesis.”

Cummings’ studies, done in collaboration with Ryan Botts at PLNU and Eva Top at the University of Idaho, could reveal antibiotic resistance genes with the potential to move into new species of disease-causing bacteria and back into human populations. By identifying these genes and raising awareness of the problem, he hopes to aid future efforts to mitigate the spread of antibiotic resistance.