As Halloween approaches, we turned up some spectral images from our gallery. The collection below highlights some spooky-sounding—but really important—biological topics that researchers are actively investigating to spur advances in medicine.

Biomedical Beat Blog – National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Follow the process of discovery

As Halloween approaches, we turned up some spectral images from our gallery. The collection below highlights some spooky-sounding—but really important—biological topics that researchers are actively investigating to spur advances in medicine.

We asked the heads of our scientific divisions to tell us about some of the big questions in fundamental biomedical science that researchers are investigating with NIGMS support. This article is the second in an occasional series that explores these questions and explains how pursuing the answers could advance understanding of important biological processes.

For some health conditions, the cause is clear: A single altered gene is responsible. But for many others, the path to disease is more complex. Scientists are working to understand how factors like genetics, lifestyle and environmental exposures all contribute to disease. Another important, but less well-known, area of investigation is the role of chance at the molecular level.

One team working in this field is led by John Tyson at Virginia Tech. The group focuses on how chance events affect the cell division cycle, in which a cell duplicates its contents and splits into two. This cycle is the basis for normal growth, reproduction and the replenishment of skin, blood and other cells throughout the body. Errors in the cycle are associated with a number of conditions, including birth defects and cancer. Continue reading “How Cells Manage Chance”

Cells are the ultimate smart material. They can sense the demands being placed on them during critical life processes and then respond by strengthening, remodeling or self-repairing, for instance. To do this, cells use “mechanosensory” systems similar to the cruise control that lets a car’s engine adjust its power output when going up or down hills.

Researchers are uncovering new details on cells’ molecular cruise control systems. By learning more about the inner workings of these systems, scientists hope ultimately to devise ways to tinker with them for therapeutic purposes.

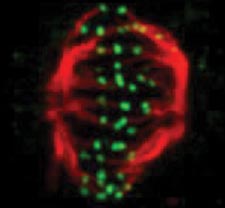

Cell Fusion

To examine how cells fine-tune their architecture and force output during the merging or fusion of cells, Elizabeth Chen and Douglas Robinson of Johns Hopkins University teamed up with Daniel Fletcher of the University of California, Berkeley. Cell fusion is critical to many developmental and physiological processes, including fertilization, placenta formation, immune response, and skeletal muscle development and regeneration.

Using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as a model system, Chen’s research group ![]() previously found that when two muscle cells merge during muscle development, fingerlike protrusions of one cell invade the territory of the other cell to promote fusion. In the new study, led by Chen, the researchers showed that cell fusion depends on the ability of the “receiving” cell to put up resistance against the invading cells.

previously found that when two muscle cells merge during muscle development, fingerlike protrusions of one cell invade the territory of the other cell to promote fusion. In the new study, led by Chen, the researchers showed that cell fusion depends on the ability of the “receiving” cell to put up resistance against the invading cells.

In fusing fruit fly cells, the scientists saw that in areas where the invading cells drilled in, the receiving cells quickly stiffened their cell skeletons, effectively pushing back. This mechanosensory response allows the outer membranes of the two cells to be pushed together and later fuse, Chen explains.

The team then explored the mechanisms underlying the stiffening response. They found that a protein called myosin II, which is part of the cell skeleton, senses the pushing force from the invading cell. Myosin II swarms to the fusion site and binds with fibers just beneath the cell membrane to put up the necessary resistance.

Continue reading “Cellular ‘Cruise Control’ Systems Let Cells Sense and Adapt to Changing Demands”

Has the “spring forward” time change left you feeling drowsy? While researchers can’t give you back your lost ZZZs, they are unraveling a long-standing mystery about sleep. Their work will advance the scientific understanding of the process and could improve ways to foster natural sleep patterns in people with sleep disorders.

Working at Massachusetts General Hospital and MIT, Christa Van Dort, Matthew Wilson, and Emery Brown focused on the stage of sleep known as REM. Our most vivid dreams occur during this period, as do rapid eye movements, for which the state is named. Many scientists also believe REM is crucial for learning and memory.

REM occurs several times throughout the night, interspersed with other sleep states collectively called non-REM sleep. Although REM is clearly necessary—it occurs in all land mammals and birds—researchers don’t really know why. They also don’t understand how the brain turns REM on and off.

Continue reading “Scientists Shine Light on What Triggers REM Sleep”

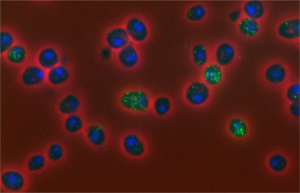

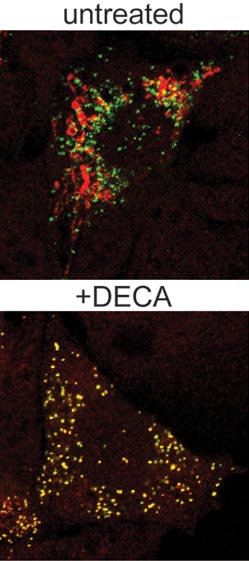

Our cells have organized systems to route newly created proteins to the places where they’re needed to do their jobs. For some people born with a rare and potentially fatal genetic kidney disorder called PH1, a genetically altered form of a particular protein mistakenly ends up in mitochondria instead of in another organelle, the peroxisome. This cellular routing error of the AGT protein results in the harmful buildup of oxalate, which leads to kidney failure and other problems at an early age.

In new work led by UCLA biochemist Carla Koehler ![]() , researchers used a robotic screening system to identify a compound that interferes with the delivery of proteins to mitochondria. Koehler’s team

, researchers used a robotic screening system to identify a compound that interferes with the delivery of proteins to mitochondria. Koehler’s team ![]() showed that adding a small amount of the compound, known as DECA, to cells grown in the laboratory prevented the altered form of the AGT protein from going to the mitochondria and sent it to the peroxisome. The compound also reduced oxalate levels in a cell model of PH1.

showed that adding a small amount of the compound, known as DECA, to cells grown in the laboratory prevented the altered form of the AGT protein from going to the mitochondria and sent it to the peroxisome. The compound also reduced oxalate levels in a cell model of PH1.

The team’s findings suggest that DECA, which is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating certain bacterial infections, could be a promising candidate for treating children affected by PH1. And, Koehler notes, the screening strategy that she and her team used to identify DECA as a potential therapy may help researchers identify other new therapies for the disorder.

This work was funded in part by NIH under grant R01GM061721.

When our health is concerned, some molecules are widely labeled “good,” while others are considered “bad.” Often, the truth is more complicated.

Consider free radical molecules. These highly reactive, oxygen-containing molecules are well known for damaging DNA, proteins and other molecules in our bodies. They are suspected of contributing to premature aging and cancer. But now, new research shows they might also have healing powers.

Using the oft-studied laboratory roundworm known as C. elegans, a research group led by Andrew Chisholm at the University of California, San Diego, made a surprising discovery. Free radicals, specifically those made in cell structures called mitochondria, appear necessary for skin wounds to heal. In fact, higher (but not dangerously high) levels of the molecules can actually speed wound closure.

If further research shows the same holds true in humans, the work could point to new ways to treat hard-to-heal wounds, like diabetic foot ulcers.

This work was funded in part by NIH under grants R01GM054657 and P40OD010440.

Cells are the basic unit of life—and the focus of much scientific study and classroom learning. Here are just a few of their fascinating facets.

3.8 billion

That’s how many years ago scientists believe the first known cells originated on Earth. These were prokaryotes, single-celled organisms that do not have a nucleus or other internal structures called organelles. Bacteria are prokaryotes, while human cells are eukaryotes.

0.001 to 0.003

This is the diameter in centimeters of most animal cells, making them invisible to the naked eye. There are some exceptions, such as nerve cells that can stretch from our hips to our toes, sending electrical signals throughout the body.

1665

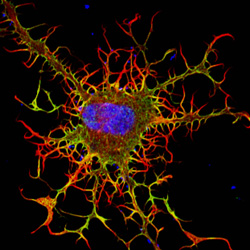

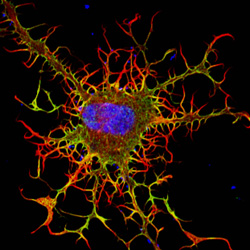

In that year, British scientist Robert Hooke coined the term cell to describe the porous, grid-like structure he saw when viewing a thin slice of cork under a microscope. Today, scientists study cells using a variety of high-tech imaging equipment as well as rainbow-colored dyes and a green fluorescent protein derived from jellyfish.

200

That’s how many different types of cells are in the human body, including those in our skin, muscles, nerves, intestines, blood and bones.

3 to 5

Believe it or not, that’s the approximate number of pounds of bacteria you’re carrying around, depending on your size. Even though bacterial cells greatly outnumber ours, they’re much smaller than our cells and therefore account for less than 3 percent of our body mass. Scientists are learning more about how our body bacteria contribute to our health.

24

This is the typical length in hours of the animal cell cycle, the time from a cell’s formation to when it splits in two to make more cells.

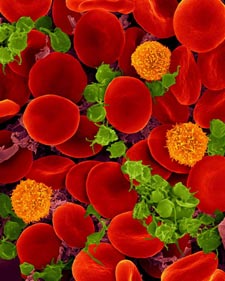

120

That’s the approximate lifespan in days of a human red blood cell. Other cell types have different lifespans, from a few weeks for some skin cells to as long as the life of the organism for healthy neurons.

50 to 70 billion

Each day, approximately this many cells die in the human body as part of a normal process that serves a healthy and protective role. Those that die in the largest numbers are skin cells, blood cells and some cells that line structures like organs and glands.

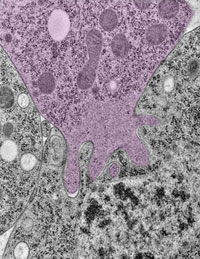

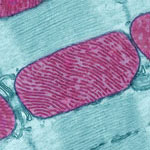

Meet mitochondria: cellular compartments, or organelles, that are best known as the powerhouses that convert energy from the food we eat into energy that runs a range of biological processes.

As you can see in this close-up of mitochondria from a rat’s heart muscle cell, the organelles have an inner membrane that folds in many places (and that appears here as striations). This folding vastly increases the surface area for energy production. Nearly all our cells have mitochondria, but cells with higher energy demands have more. For instance, a skin cell has just a few hundred, while the cell pictured here has about 5,000.

Scientists are discovering there’s more to mitochondria than meets the eye, especially when it comes to understanding and treating disease.

Read more about mitochondria in this Inside Life Science article.

In this image, the optic nerve (left) leaves the back of the retina (right). Where the retina meets the optic nerve, visual information begins its journey from the eye to the brain. Taking a closer look, axons (purple), which carry electrical and chemical messages, meet astrocytes (yellow), a type of brain cell. Recent research has found a new and surprising role for these astrocytes.

Biologists have long thought that all cells, including neurons, degrade and reuse pieces of their own mitochondria, the little powerhouses that provide energy to cells. Using cutting-edge imaging technology, researchers led by Mark Ellisman of the University of California, San Diego, and Nicholas Marsh-Armstrong of Johns Hopkins University have caught neurons in the mouse optic nerve in the act of passing some of their worn out mitochondria to neighboring astrocytes, which then did the dirty work of recycling.

The researchers also showed that neurons in other regions of the brain appear to outsource mitochondrial breakdown to astrocytes as well. They suggest that it will be important to confirm that this process occurs in other parts of the brain and to determine how possible defects in the outsourcing may contribute to or underlie neuronal dysfunction or neurodegenerative diseases.

This work also was funded by NIH’s National Eye Institute and National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Learn more:

University of California, San Diego News Release and Blog Posting

How Cells Take Out the Trash Article from Inside Life Science

Nerve cells (neurons) in the brain use small molecules called neuropeptides to converse with each other. Disruption of this communication can lead to problems with learning, memory and other brain functions. Through genetic studies in a model organism, the tiny worm C. elegans, a team led by Kenneth Miller of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation has uncovered a previously unknown mechanism that nerve cells use to package, move and release neuropeptides. The researchers found that a protein called CaM kinase II, which plays many roles in the brain, helps control this mechanism. Neuropeptides in worms lacking CaM kinase II spilled out from their packages before they reached their proper destinations. A more thorough understanding of how neurons work, provided by studies like this, may help researchers better target drugs to treat memory disorders and other neurological problems in humans.

This work also was funded by NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health.

Learn more:

Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation News Release ![]()