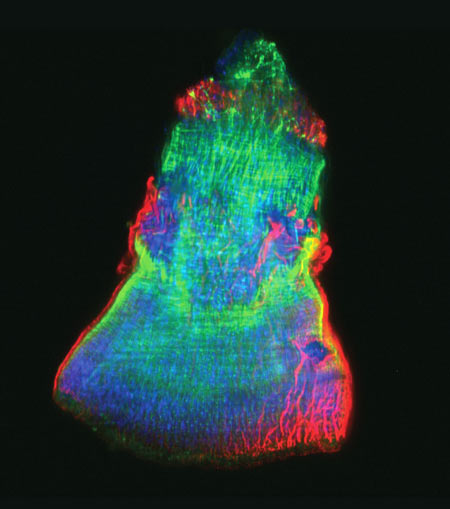

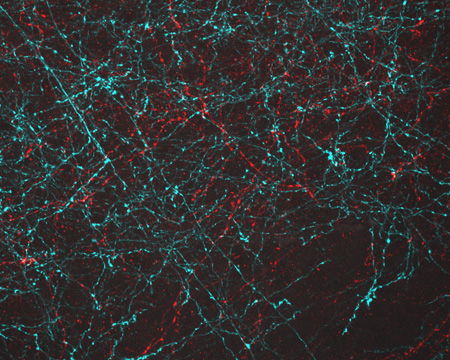

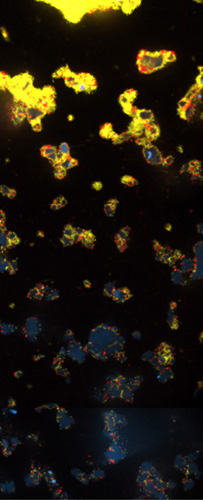

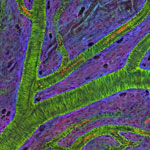

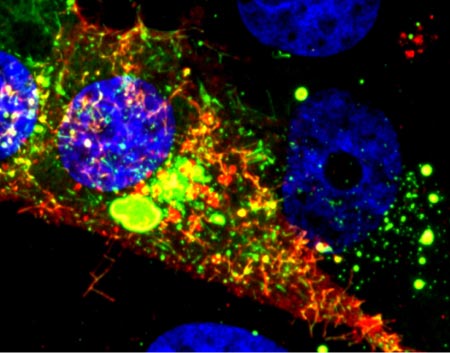

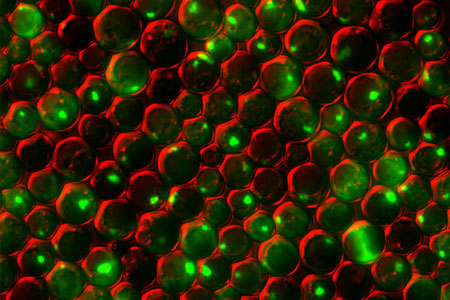

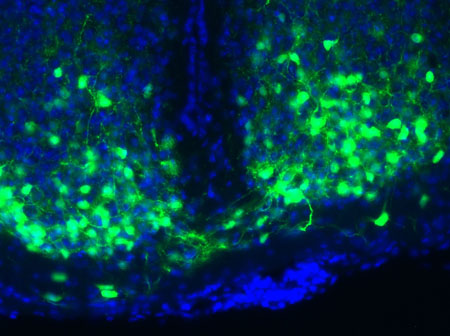

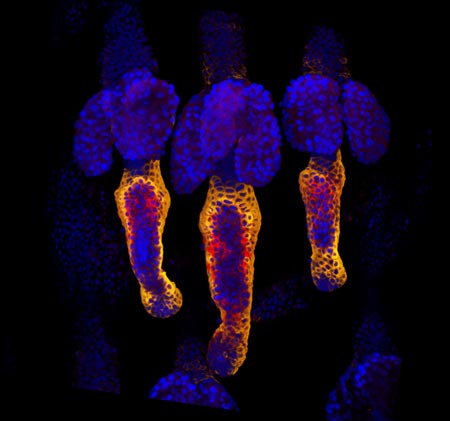

Science. Art. Airports. I’ve never used those three words together before. But I’ve been doing it a lot lately while working on Life: Magnified, an exhibit of 46 striking scientific images created by scientists around the country using state-of-the-art microscopes.

The show is at Washington Dulles International Airport, where more than a million travelers will see it over its 6-month run. As our director said in a recent post on another NIGMS blog, “What a great way to share the complexity and beauty of biomedical science with such a large public audience!”

We’ve also set up an online gallery, where the colorful images can be viewed and freely downloaded for research, educational and news media purposes.

The project itself was quite an adventure. When we asked scientists to send us images, our fears of not getting enough attractive, high-resolution options were drowned by a deluge of more than 600 submissions. Then we worried how to sort through them all and make final selections. Doing so required several rounds of online viewing, various ranking systems and a panel of experts. Then the images were printed as large, digital negatives on transparency film.

Dulles is a pretty busy place, so we set up the exhibit when it was quietest—the middle of the night (10 p.m. to 1:30 a.m., to be exact). We swapped out images from the previous photography exhibit and installed the Life: Magnified ones in LED lightboxes mounted in the airport’s Gateway Gallery. It was an eerie and exhilarating feeling to be in a noiseless, nearly empty airport without heavy bags and a long walk to a departure gate.

Less than 12 hours later, I was surprised to receive an e-mail from someone who had passed through the exhibit and sent a few photos. He called the images “stunning.” Similar sentiments were expressed by Science, NBC News online ![]() , The Atlantic

, The Atlantic ![]() , The Washington Post

, The Washington Post ![]() , National Geographic

, National Geographic ![]() and other publications.

and other publications.

Now I’m being asked about next steps, including whether the exhibit will travel. We’re investigating a variety of options. For now, I hope you’re able to see the exhibit in person. If not, take a look at the images online and see which ones you enjoy most.