Cells are the ultimate smart material. They can sense the demands being placed on them during critical life processes and then respond by strengthening, remodeling or self-repairing, for instance. To do this, cells use “mechanosensory” systems similar to the cruise control that lets a car’s engine adjust its power output when going up or down hills.

Researchers are uncovering new details on cells’ molecular cruise control systems. By learning more about the inner workings of these systems, scientists hope ultimately to devise ways to tinker with them for therapeutic purposes.

Cell Fusion

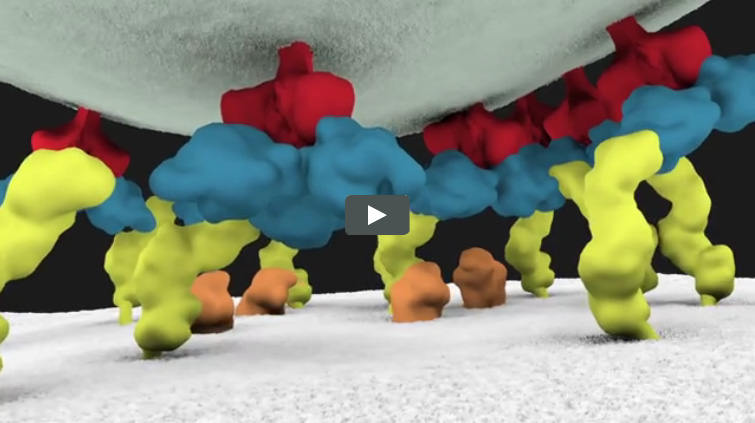

To examine how cells fine-tune their architecture and force output during the merging or fusion of cells, Elizabeth Chen and Douglas Robinson of Johns Hopkins University teamed up with Daniel Fletcher of the University of California, Berkeley. Cell fusion is critical to many developmental and physiological processes, including fertilization, placenta formation, immune response, and skeletal muscle development and regeneration.

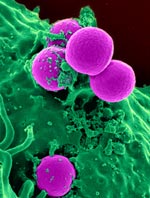

Using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster as a model system, Chen’s research group ![]() previously found that when two muscle cells merge during muscle development, fingerlike protrusions of one cell invade the territory of the other cell to promote fusion. In the new study, led by Chen, the researchers showed that cell fusion depends on the ability of the “receiving” cell to put up resistance against the invading cells.

previously found that when two muscle cells merge during muscle development, fingerlike protrusions of one cell invade the territory of the other cell to promote fusion. In the new study, led by Chen, the researchers showed that cell fusion depends on the ability of the “receiving” cell to put up resistance against the invading cells.

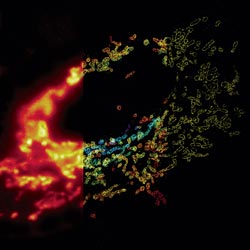

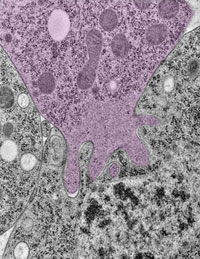

In fusing fruit fly cells, the scientists saw that in areas where the invading cells drilled in, the receiving cells quickly stiffened their cell skeletons, effectively pushing back. This mechanosensory response allows the outer membranes of the two cells to be pushed together and later fuse, Chen explains.

The team then explored the mechanisms underlying the stiffening response. They found that a protein called myosin II, which is part of the cell skeleton, senses the pushing force from the invading cell. Myosin II swarms to the fusion site and binds with fibers just beneath the cell membrane to put up the necessary resistance.

Continue reading “Cellular ‘Cruise Control’ Systems Let Cells Sense and Adapt to Changing Demands”