Bacteria can cause many common illnesses, including strep throat and ear infections. If you’ve ever gone to the doctor for one of these infections, they likely prescribed an antibiotic—a medicine designed to fight bacteria. Because bacteria can also cause life-threatening infections, antibiotics have saved many lives. However, the widespread use of antibiotics has fueled a growing problem: antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria can survive some or even all antibiotics. Other microorganisms, including fungi, can similarly become resistant to the medicines that are used to treat them. Infections from these microorganisms affect many people and are difficult to treat. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the U.S. alone, resistant bacteria and fungi infect 2.8 million people each year, and more than 35,000 die as a result.

How Bacteria Escape Antibiotics

Antibiotics can kill bacteria in a few different ways. The most common include blocking bacteria’s ability to build or maintain their cell walls and blocking the production of molecules, like proteins or nucleic acids, that they need to grow. However, anytime bacteria encounter antibiotics, there’s a chance some will mutate in a way that enables them to survive those medicines, making them antibiotic resistant. How do mutations provide antibiotic resistance? They might cause bacteria to:

- Produce enzymes that destroy antibiotics or make them ineffective

- Change parts of the cells that antibiotics target so that the antibiotics can’t do their jobs

- Develop new ways of functioning that bypass the cellular processes affected by an antibiotic

- Alter or reduce cell entry so that it’s more difficult for antibiotics to get into cells

- Build pumps in their cell walls that push out antibiotics that get inside

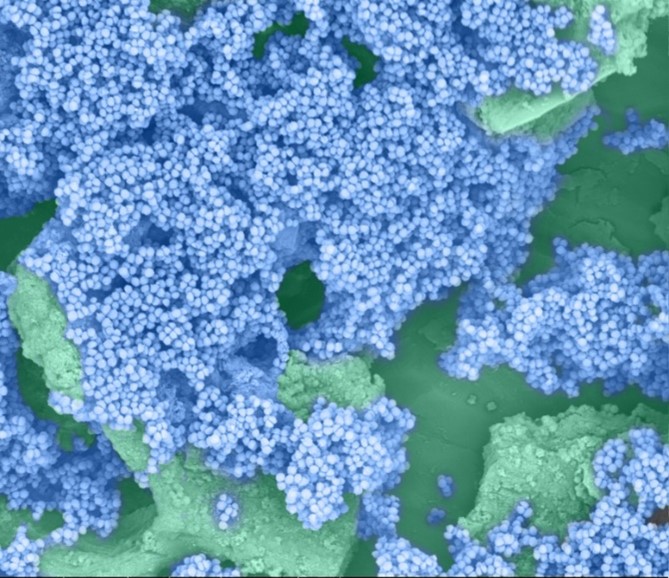

Bacteria can organize into biofilms, which can be helpful to humans in certain situations but harmful when they form inside the body. (More on biofilms in this previous post.) Biofilms are much more resistant to antibiotics than individual bacteria are, but scientists are still trying to understand why. Their slimy surfaces are hard to penetrate and the environments underneath are very different from the host—both of which may keep the antibiotic from working properly.

Fighting Antibiotic Resistance

Because of the risk of antibiotic resistance, doctors prescribe antibiotics only when they can make a difference. They won’t, for example, prescribe antibiotics when a person has a viral infection, such as a cold or the flu, because antibiotics don’t kill viruses. It’s also important for you, as a patient, to take antibiotics correctly. When someone doesn’t take antibiotics for as long as their doctor tells them to, it’s more likely that some bacteria will survive and develop resistance. If antibiotic-resistant bacteria arise, they could make the person sicker or spread to other people.

In addition to taking antibiotics as instructed, you can help prevent antibiotic-resistant infections by:

- Never sharing antibiotics that were prescribed to you with someone else—or taking antibiotics prescribed to someone else

- Bringing any antibiotics leftover after taking the full prescribed course to a local collection site for disposal so they don’t end up in local water or soil and affect the bacteria that live there

- Taking steps to reduce the risk of getting a bacterial infection, such as washing your hands, keeping cuts clean and covered, and staying up to date on vaccinations

- Staying home when you feel sick to reduce the risk of spreading infections to others

Many researchers, including those with support from NIGMS, are working on new ways to combat antibiotic-resistant infections. Combined, our efforts and theirs can help lessen the impact of these infections and keep us all healthy.

This post is a great supplement to the Pathways issue on superbugs.

Both this post and Pathways discuss antibiotic resistance.

Learn more in our Educator’s Corner.