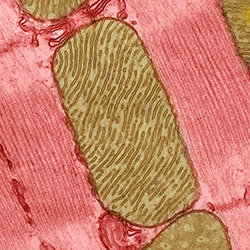

In part I of this series, we mentioned that the extracellular matrix (ECM) makes our tissues stiff or squishy, solid or see-through. Here, we reveal how the ECM helps body cells move around, a process vital for wounds to heal and a fetus to grow.

Sealing and Healing Wounds

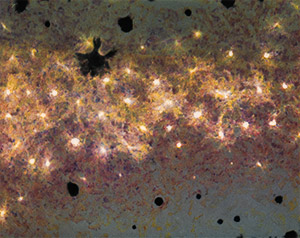

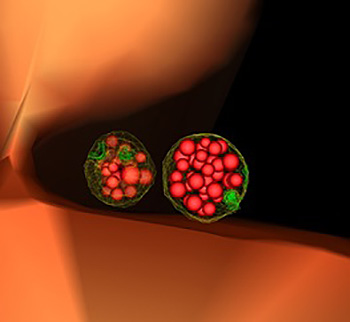

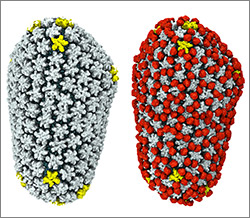

When we get injured, the first thing our body does is to form a blood clot to stop the bleeding. Skin cells then start migrating into the wound to close the cut. The ECM is essential for this step, creating a physical support structure—like a road or train track—over which skin cells travel to seal the injured spot.

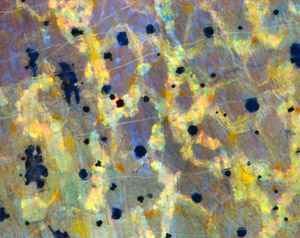

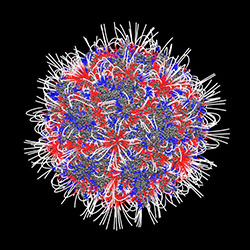

The ECM is made up of a host of proteins produced before and after injury. Some other proteins called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) also crowd into wounds. Because humans have so many different MMPs—a full 24 of them!—it’s been difficult for scientists to figure out what roles, if any, the proteins play in healing scrapes and cuts.

Continue reading “The ECM: A Dynamic System for Moving Our Cells”