Zebrafish, blue-and-white-striped fish that are about 1.5 inches long, can regrow injured or lost fins. This feature makes the small fish a useful model organism for scientists who study tissue regeneration.

To better understand how zebrafish skin recovers after a scrape or amputation, researchers led by Kenneth Poss of Duke University tracked thousands of skin cells in real time. They found that lifespans of individual skin cells on the surface were 8 to 9 days on average and that the entire skin surface turned over in 20 days.

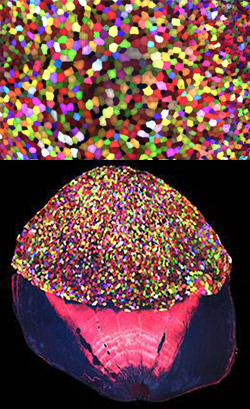

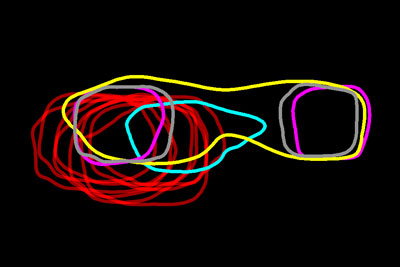

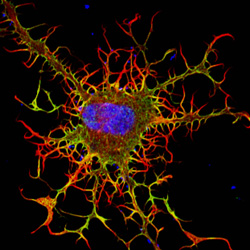

The scientists used an imaging technique they developed called “Skinbow,” which essentially shows the fish’s outer layer of skin cells in a spectrum of colors when viewed under a microscope. Skinbow is based on a technique created to study nerve cells in mice, another model organism.

The research team’s color-coded experiments revealed several unexpected cellular responses during tissue repair and replacement. The scientists plan to incorporate additional imaging techniques to generate an even more detailed picture of the tissue regeneration process.

The NIH director showcased the Skinbow technique and these images on his blog, writing: “You can see more than 70 detectable Skinbow colors that make individual cells as visually distinct from one another as jellybeans in a jar.”

This work was funded in part by NIH under grant R01GM074057.

On November 5, we’ll host my favorite NIGMS science education event: Cell Day! As in previous years, we hope this free, interactive Web chat geared for middle and high school students will spark interest in cell biology, biochemistry and research careers. Please help us spread the word by letting people in your local schools and communities know about this special event and encouraging them to register. It runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. EST and is open to all.

On November 5, we’ll host my favorite NIGMS science education event: Cell Day! As in previous years, we hope this free, interactive Web chat geared for middle and high school students will spark interest in cell biology, biochemistry and research careers. Please help us spread the word by letting people in your local schools and communities know about this special event and encouraging them to register. It runs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. EST and is open to all.