We asked the heads of our scientific divisions to tell us about some of the big questions in fundamental biomedical science that researchers are investigating with NIGMS support. This article is the second in an occasional series that explores these questions and explains how pursuing the answers could advance understanding of important biological processes.

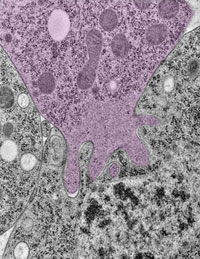

For some health conditions, the cause is clear: A single altered gene is responsible. But for many others, the path to disease is more complex. Scientists are working to understand how factors like genetics, lifestyle and environmental exposures all contribute to disease. Another important, but less well-known, area of investigation is the role of chance at the molecular level.

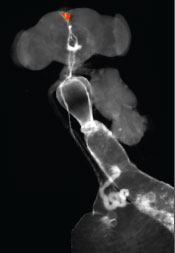

One team working in this field is led by John Tyson at Virginia Tech. The group focuses on how chance events affect the cell division cycle, in which a cell duplicates its contents and splits into two. This cycle is the basis for normal growth, reproduction and the replenishment of skin, blood and other cells throughout the body. Errors in the cycle are associated with a number of conditions, including birth defects and cancer. Continue reading “How Cells Manage Chance”