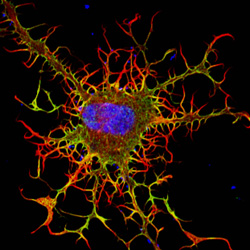

Credit: Kristan Jacobsen

Nels Elde, Ph.D.

Fields: Evolutionary genetics, virology, microbiology, cell biology

Works at: University of Utah, Salt Lake City

When not in the lab, he’s: Gardening, supervising pets, procuring firewood

Hobbies: Canoeing, skiing, participating in facial hair competitions

“I really look at my job as an adventure,” says Nels Elde. “The ability to follow your nose through different fields is what motivates me.”

Elde has used that approach to weave evolutionary genetics, bacteriology, virology, genomics and cell biology into his work. While a graduate student at the University of Chicago and postdoctoral researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, he became interested in how interactions between pathogens (like viruses and bacteria) and their hosts (like humans) drive the evolution of both parties. He now works in Salt Lake City, where, as an avid outdoorsman, he draws inspiration from the wild landscape.

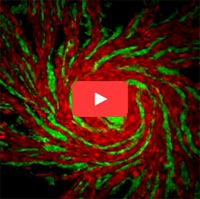

Outside the lab, Elde keeps diverse interests and colorful company. His best friend wrote a song about his choice of career as a cell biologist. (You can hear this song at the end of the 5-minute video  in which Elde explains his work.) Continue reading “Meet Nels Elde and His Team’s Amazing, Expandable Viruses”

in which Elde explains his work.) Continue reading “Meet Nels Elde and His Team’s Amazing, Expandable Viruses”