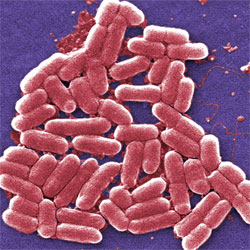

Bacteria hold a vast reservoir of compounds with therapeutic potential. They use these compounds, known as secondary metabolites, to protect themselves against their enemies. We use them in many antibiotics, anti-inflammatories and other treatments.

Scientists interested in developing new medicines have no shortage of places to look for secondary metabolites. There are an estimated 120,000 to 150,000 bacterial species on Earth. Each species is capable of producing hundreds of secondary metabolites, but often only under specific ecological conditions. The challenge for researchers is figuring out how to coax the bacteria to produce these compounds.

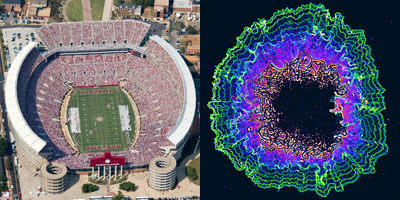

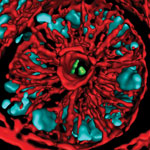

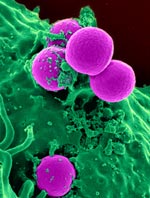

Now, Brian Bachmann and John McLean of Vanderbilt University and their teams have shown that by creating “fight clubs” where bacteria compete with one another, they can trigger the bacteria to make a wide diversity of molecules, including secondary metabolites. Continue reading “Bacterial ‘Fight Clubs’ and the Search for New Medicines”