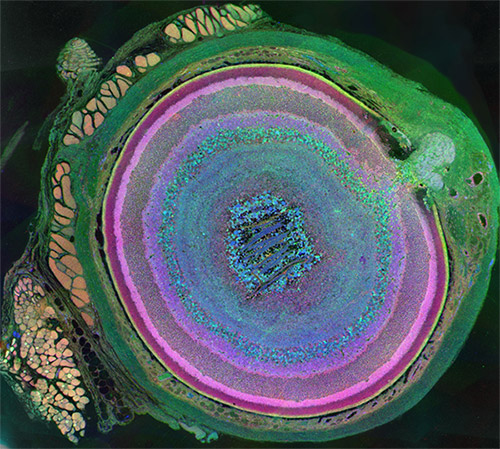

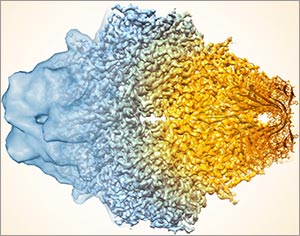

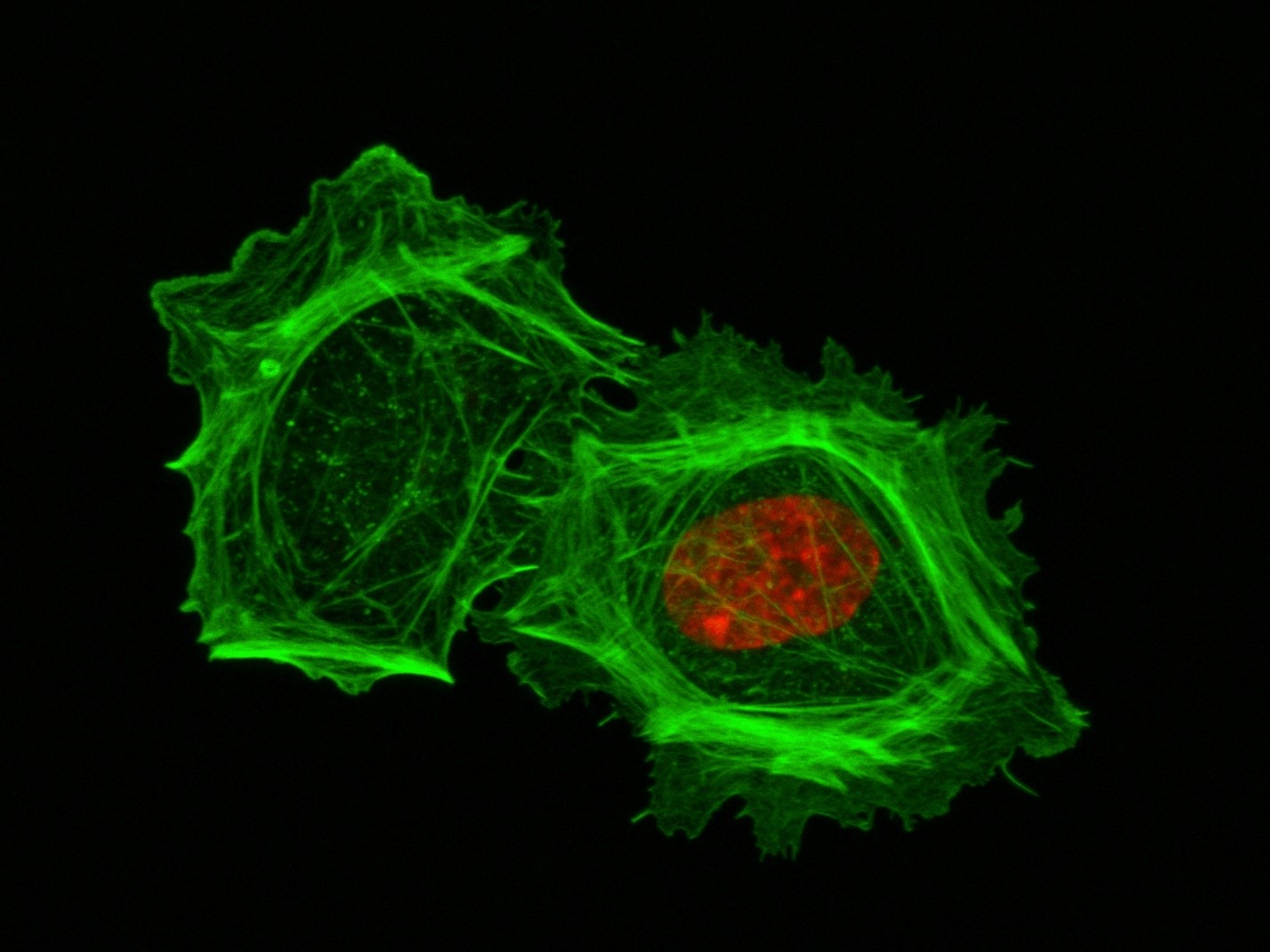

These two human cells are nearly identical, except that the cell on the left had its nucleus (dyed red) removed. The structures dyed green are protein strands that give cells their shape and coherence. Credit: David Graham, UNC-Chapel Hill.

These two human cells are nearly identical, except that the cell on the left had its nucleus (dyed red) removed. The structures dyed green are protein strands that give cells their shape and coherence. Credit: David Graham, UNC-Chapel Hill.Both of the cells above can scoot across a microscope slide equally well. But when it comes to moving in 3D, the one without the red blob in the center (the nucleus) stalls out. That’s sort of like an Olympic speed skater who wouldn’t be able to perform even a single leap in a figure skating competition.

Scientists have known for some time that the nucleus is involved in moving cells across a flat surface—it slides to one side of the cell and “pushes” from behind. However, scientists have also shown that cells with their nuclei removed can migrate along a flat surface just as well as their brethren with intact nuclei. But they had no idea that, without a nucleus, a cell could no longer move in three dimensions.

This discovery was made by UNC-Chapel Hill biologists Keith Burridge and James Bear and their colleagues. These NIGMS-funded researchers also observed that cells whose nuclei had been disconnected from the cytoskeleton could not move through 3D matrices. The cytoskeleton is the microscopic network of actin protein filaments and tubules in the cytoplasm of many cells that provides the cell’s shape and coherence. It has also has been thought to play a major role in cell movement.

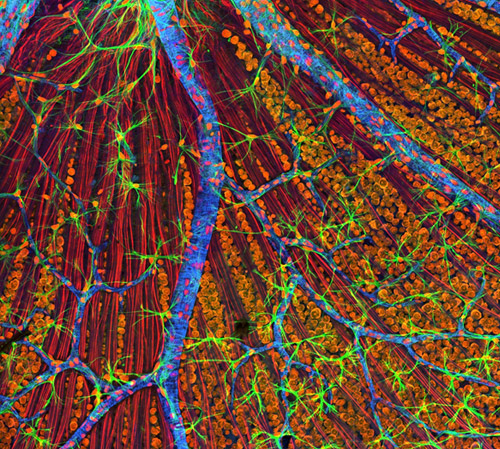

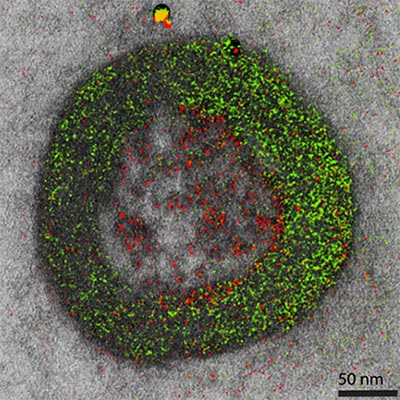

The gray, stringy background of these videos is a 3D jello-like matrix. The cell in the top half of this video has a nucleus and can migrate through the matrix. Both cells in the bottom half have been enucleated (a fancy term for having its nucleus removed) and cannot travel through the matrix. Credit: Graham et al., Journal of Cell Biology, 2018.

The gray, stringy background of these videos is a 3D jello-like matrix. The cell in the top half of this video has a nucleus and can migrate through the matrix. Both cells in the bottom half have been enucleated (a fancy term for having its nucleus removed) and cannot travel through the matrix. Credit: Graham et al., Journal of Cell Biology, 2018.The researchers speculate that the reason cells without nuclei (or those whose nuclei have been disconnected from the cytoskeleton) don’t navigate in 3D has to do with complex mechanical interactions between the cytoskeleton and the nucleoskeleton. The nucleoskeleton is a molecular scaffold within the nucleus supporting many functions such as DNA replication and transcription, chromatin remodeling, and mRNA synthesis. The interface between the cytoskeleton and nucleoskeleton consists of interlocking proteins that together provide the physical traction that cells need to push their way through 3D environments. Disrupting this interface is the equivalent of breaking the clutch in a car: the motor revs, but the wheels don’t spin, and the car goes nowhere.

A better understanding of the physical connections between the nucleus and the cytoskeleton and how they influence cell migration may provide additional insight into the role of the nucleus in diseases, such as cancer, in which the DNA-containing organelle is damaged or corrupted.

This research was funded in part by NIGMS grants 5R01GM029860-35, 5P01GM103723-05, and 5R01GM111557-04.