Credit: Denise Applewhite.

Laura Landweber

Grew up in: Princeton, New Jersey

Job site: Columbia University, New York City

Favorite food: Dark chocolate and dark leafy greens

Favorite music: 1940’s style big band jazz

Favorite hobby: Swing dancing

If I weren’t a scientist I would be a: Chocolatier (see “Experiments in Chocolate” sidebar at bottom of story)

One day last fall, molecular biologist Laura Landweber surveyed the Princeton University lab where she’d worked for 22 years. She and her team members had spent many hours that day laboriously affixing yellow Post-it notes to the laboratory equipment—microscopes, centrifuges, computers—they would bring with them to Columbia University, where Landweber had just been appointed full professor. Each Post-it specified the machinery’s location in the new lab. Items that would be left behind—glassware, chemical solutions, furniture, office supplies—were left unlabeled.

As Landweber viewed the lab, decorated with a field of sunny squares, her thoughts turned to another sorting process—the one used by her primary research subject, a microscopic organism, to sift through excess DNA following mating. Rather than using Post-it notes, the creature, a type of single-celled organism called a ciliate, uses small pieces of RNA to tag which bits of genetic material to keep and which to toss.

Landweber is particularly fond of Oxytricha trifallax, a ciliate with relatives that live in soil, ponds and oceans all over the world. The kidney-shaped cell is covered with hair-like projections called cilia that help it move around and devour bacteria and algae. Oxytricha is not only bizarre in appearance, it’s also genetically creative.

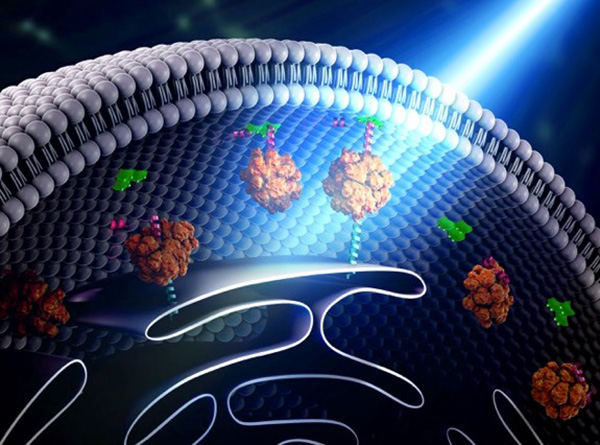

Unlike humans, whose cells are programmed to die rather than pass on genomic errors, Oxytricha cells appear to delight in genomic chaos. During sexual reproduction, the ciliate shatters the DNA in one of its two nuclei into hundreds of thousands of pieces, descrambles the DNA letters, throws most away, then recombines the rest to create a new genome.

Landweber has set out to understand how—and possibly why—Oxytricha performs these unusual genomic acrobatics. Ultimately, she hopes that learning how Oxytricha rearranges its genome can illuminate some of the events that go awry during cancer, a disease in which the genome often suffers significant reorganization and damage.

Oxytricha’s Unique Features

Oxytricha carries two separate nuclei—a macronucleus and a micronucleus. The macronucleus, by far the larger of the two, functions like a typical genome, the source of gene transcription for proteins. The tiny micronucleus only sees action occasionally, when Oxytricha reproduces sexually.

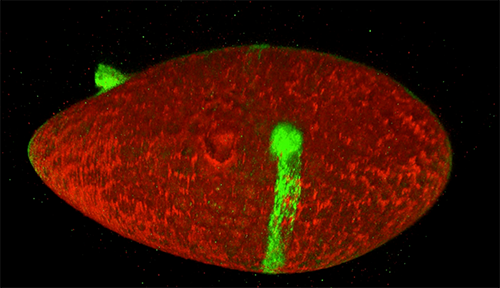

Two Oxytricha trifallax cells in the process of mating. Credit, Robert Hammersmith.

What really makes Oxytricha stand out is what it does with its DNA during the rare occasions that it has sex. When food is readily available, Oxytricha procreates without a partner, like a plant grown from a cutting. But when food is scarce, or the cell is stressed, it seeks a mate. When two Oxytricha cells mate, the micronuclear genomes in each cell swap DNA, then replicate. One copy of the new hybrid micronucleus remains intact, while the other breaks its DNA into hundreds of thousands of pieces, some of which are tagged, recombined, then copied another thousand-fold to form a new macronucleus. Continue reading “Genomic Gymnastics of a Single-Celled Ciliate and How It Relates to Humans”

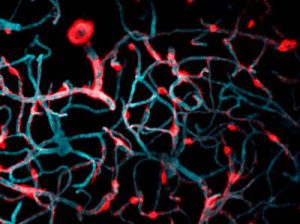

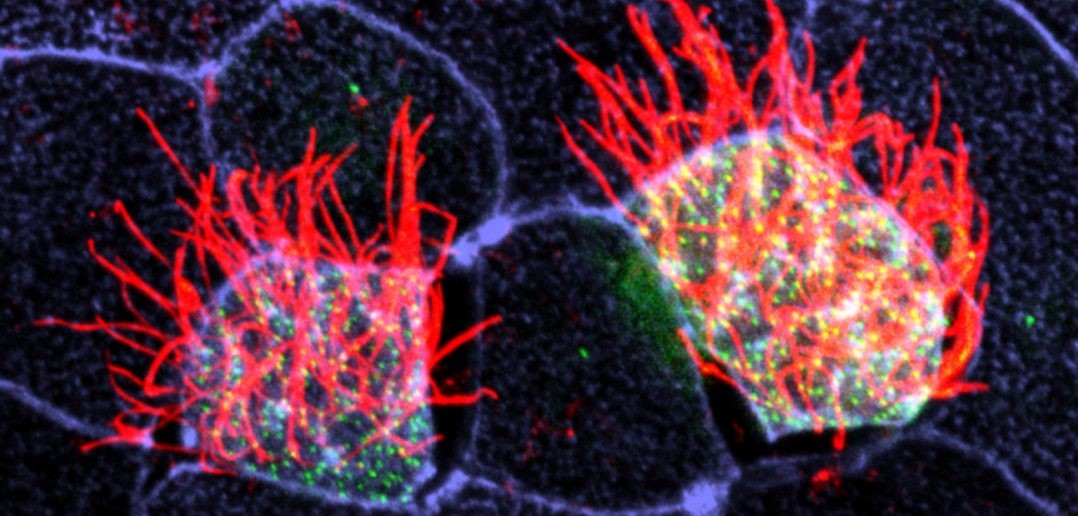

Cells covered with cilia (red strands) on the surface of frog embryos. Credit: The Mitchell Lab.

Cells covered with cilia (red strands) on the surface of frog embryos. Credit: The Mitchell Lab.