Most cells are naturally colorless, which is why scientists often use fluorescent tags and other tools to color cell structures and make them easier to study. (Check out the Pathways imaging issue for more on scientific imaging techniques). Here, we’re showcasing cell images that feature shades of blue. Visit our Image and Video Gallery for additional images of cells in all the colors of the rainbow, as well as other scientific photos, illustrations, and videos.

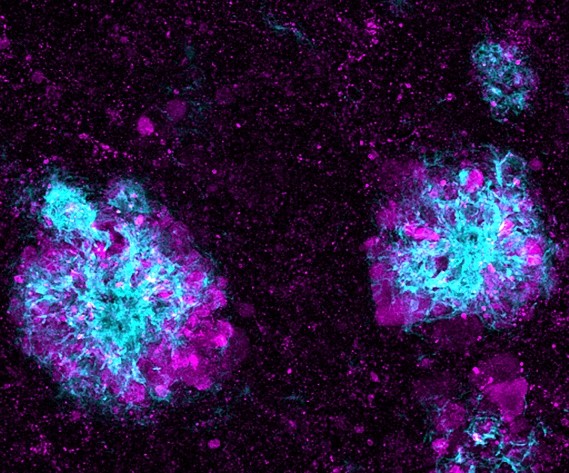

This image shows lysosomes (purple) within nerve cells that surround amyloid plaques (blue) in a research model of Alzheimer’s disease. Lysosomes help the body dispose of proteins and other molecules that have become damaged or worn out. Scientists have linked the accumulation of lysosomes around amyloid plaques to impaired waste disposal in nerve cells. This impairment ultimately causes nerve cell death, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

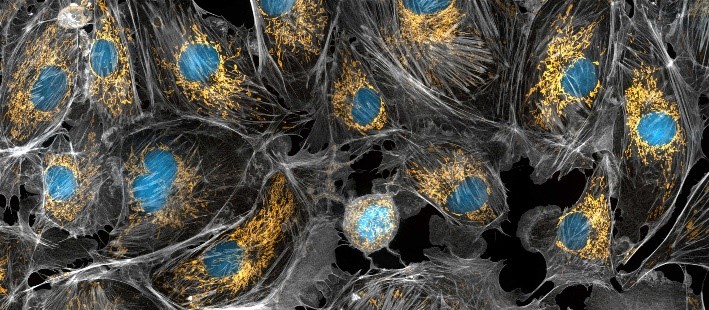

Mitochondria appear in yellow and cell nuclei in blue in this photo of cow cells. The gray webs are the cells’ cytoskeletons. Mitochondria generate energy, nuclei store DNA, and the cytoskeleton gives cells shape and support.

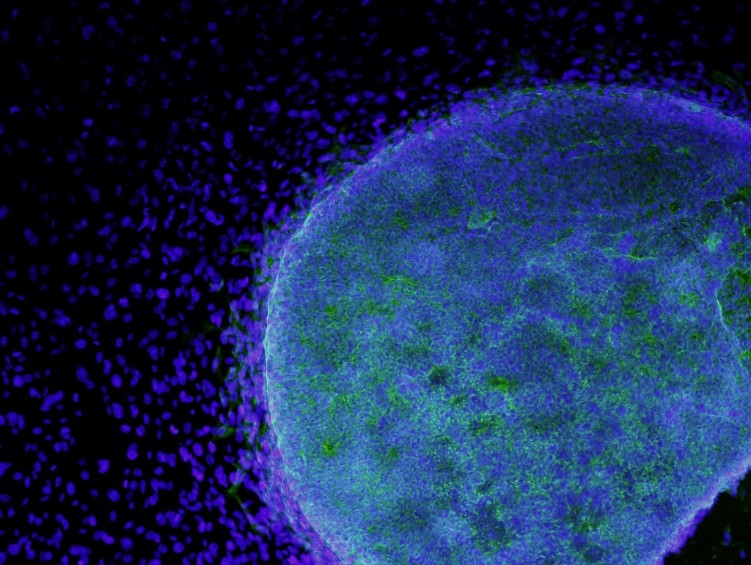

Here, stem cells (light blue) are growing on fibroblasts (dark blue). Stem cells are of great interest to researchers because they can develop into many different cell types. Fibroblasts are the most common cell type in connective tissue. They secrete collagen proteins that help build structural frameworks, and they play an important role in wound healing.

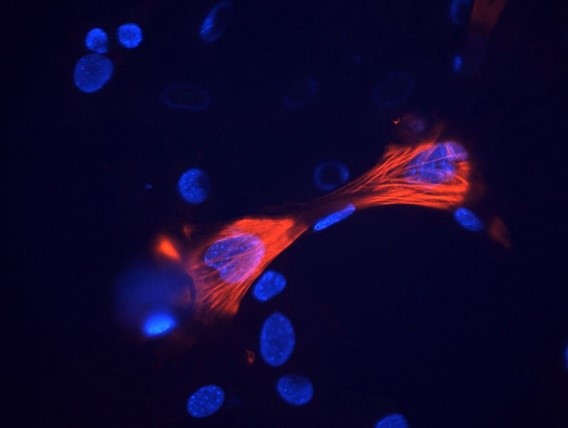

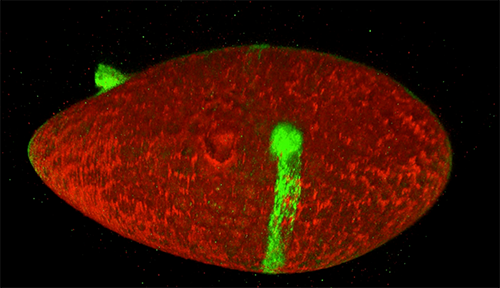

These smooth muscle cells were grown from stem cells. Smooth muscle cells are found in the walls of certain organs, such as the stomach, and can’t be controlled voluntarily. Red indicates smooth muscle proteins, and blue indicates nuclei.

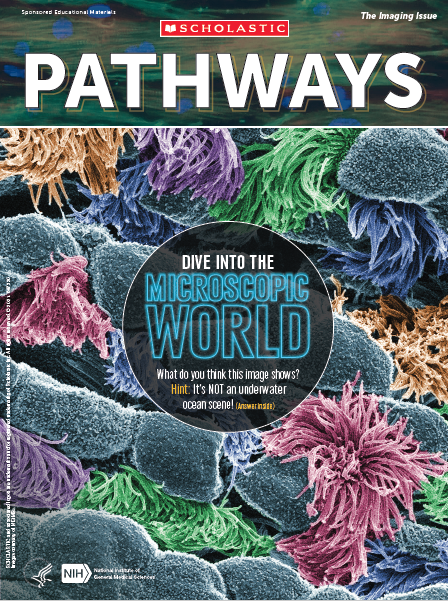

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

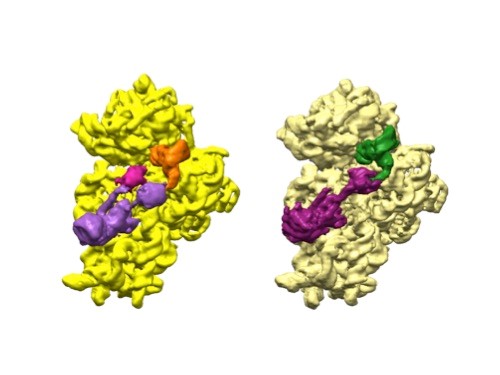

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.

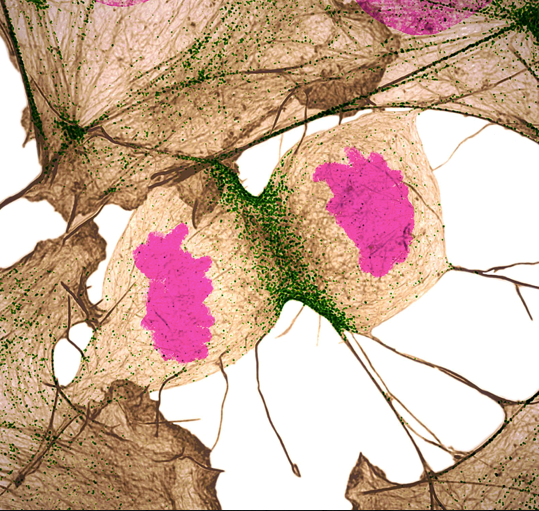

Credit: Nilay Taneja, Vanderbilt University, and Dylan T. Burnette, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Credit: Nilay Taneja, Vanderbilt University, and Dylan T. Burnette, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Firefly. Credit: Stock photo.

Firefly. Credit: Stock photo.