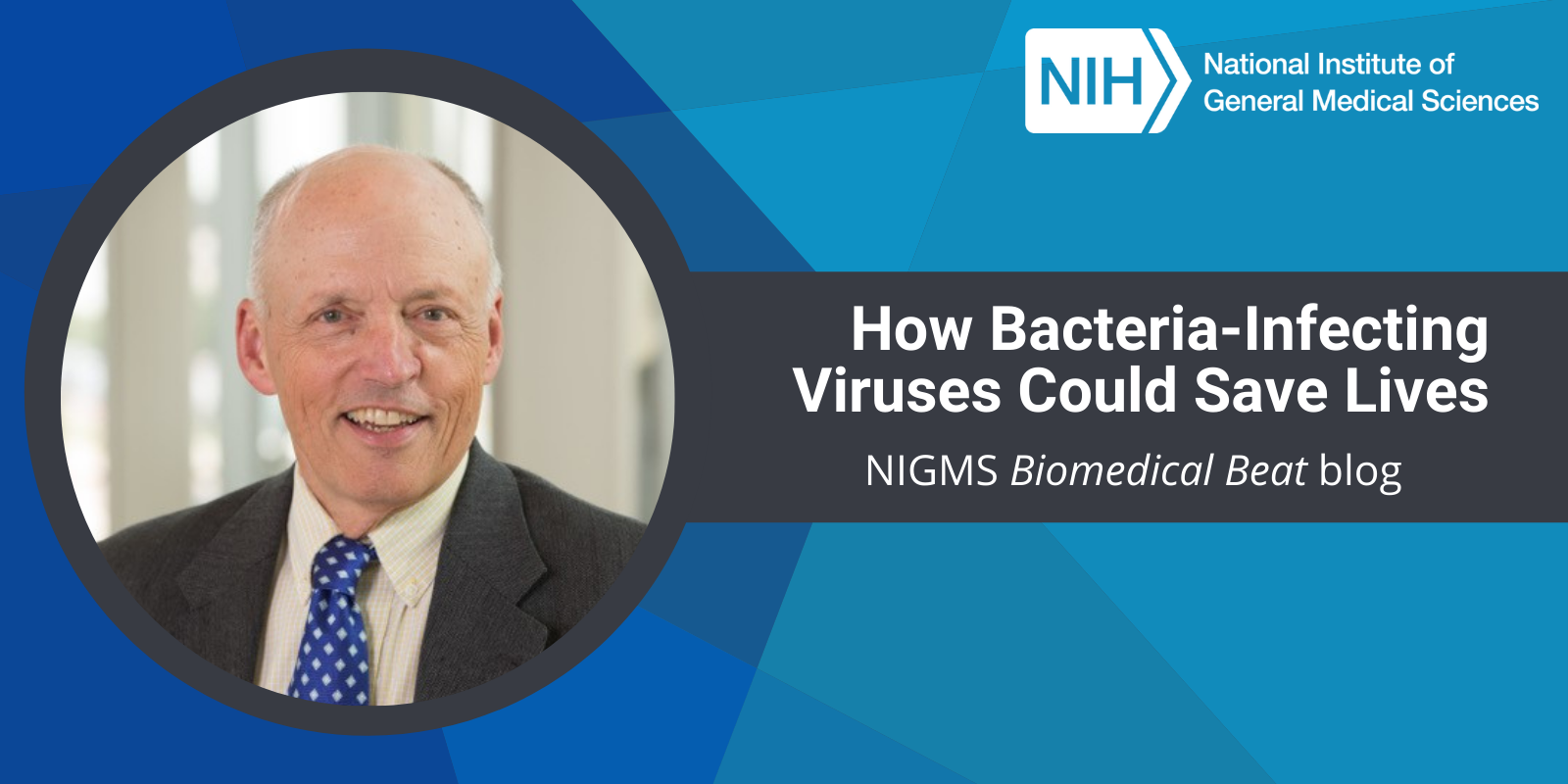

“My parents told me that I already wanted to be a scientist when I was 7 or 8 years old. I don’t remember ever considering anything else,” says Ry Young, Ph.D., a professor of biochemistry, biophysics, and biology at Texas A&M University, College Station.

Dr. Young has been a researcher for more than 45 years and is a leading expert on bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria. He and other scientists have shown that phages, as bacteriophages are often called, could help us fight bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics. Antibiotic-resistant infections cause more than 35,000 deaths per year in the U.S., and new, effective treatments for them are urgently needed.

Continue reading “How Bacteria-Infecting Viruses Could Save Lives”

Credit: Liyang Xiong and Lev Tsimring, BioCircuits Institute, UCSD.

Credit: Liyang Xiong and Lev Tsimring, BioCircuits Institute, UCSD.

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

A cone snail shell. Credit: Kerry Matz, University of Utah.

A cone snail shell. Credit: Kerry Matz, University of Utah.

View the

View the  Microbiota in the intestines. Credit: iStock.

Microbiota in the intestines. Credit: iStock.