You’ve likely heard some variation of the statistic that there are at least as many microbial cells in our body as human cells. You may have also heard that the microscopic bugs that live in our guts, on our skins, and every crevice they can find, collectively referred to as the human microbiome, are implicated in human health. But do these bacteria, fungi, archaea, protists, and viruses cause disease, or are the specific populations of microbes inside us a result of our state of health? That’s the question that drives the research in the lab of Andrew Goodman ![]() , associate professor of microbial pathogenesis at Yale University.

, associate professor of microbial pathogenesis at Yale University.

Tag: Bacteria

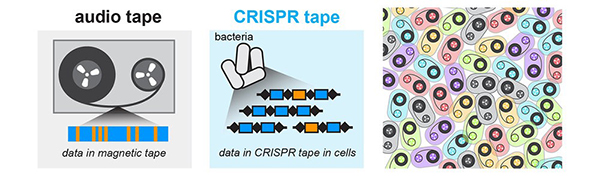

Best Documentary: Cells Record Their Own Lives Using CRISPR

Suppose you were a police detective investigating a robbery. You’d appreciate having a stack of photographs of the crime in progress, but you’d be even happier if you had a detailed movie of the robbery. Then, you could see what happened and when. Research on cells is somewhat like this. Until recently, scientists could take snapshots of cells in action, but they had trouble recording what cells were doing over time. They were getting an incomplete picture of the events occurring in cells.

Researchers have started solving this problem by combining some old knowledge—that DNA is spectacularly good at storing information—with a popular new research tool called CRISPR. CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is an immune system feature in bacteria that helps them to remember and destroy viruses that infect them. CRISPR can change DNA sequences in precise ways; and it’s programmable, meaning that researchers can tell CRISPR where to make a change on a DNA strand, and even what kind of change to make. By linking cellular events to CRISPR, researchers can make something like a movie that captures many pieces of information in the form of DNA changes that researchers can read back later. These pieces of information include timing, duration, and intensity of events, such as the turning on of a specific protein pathway or the exposure of the cell to pathogens (i.e. germs). Here, we look at some of the ways NIGMS-funded research teams and others are using CRISPR to capture these kinds of data within DNA sequences.

Round and Round: mSCRIBE Creates a Continuous Recording Loop

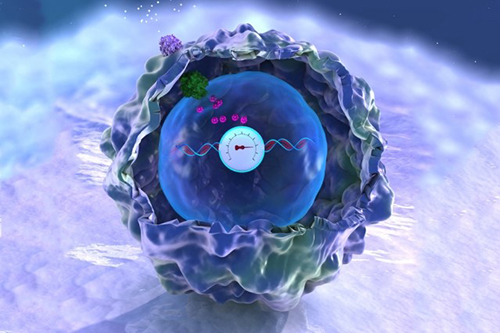

CRISPR uses an enzyme called Cas9 like a surgical knife, to slice both strands of a cell’s DNA at precise points. A cut like this sends the cell scrambling to repair the damage. Often, the repair effort results in changes, or errors, in the repaired strand that pile up at a known rate. Timothy Lu ![]() and his colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) decided to turn this cut-repair-error system into a way to record certain events inside a cell. They call their method mSCRIBE (mammalian synthetic cellular recorder integrating biological events).

and his colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) decided to turn this cut-repair-error system into a way to record certain events inside a cell. They call their method mSCRIBE (mammalian synthetic cellular recorder integrating biological events).

Continue reading “Best Documentary: Cells Record Their Own Lives Using CRISPR”

Cellular Footprints: Tracing How Cells Move

Cells are the basis of the living world. Our cells make up the tissues and organs of our bodies. Bacteria are also cells, living sometimes alone and sometimes in groups called biofilms. We think of cells mostly as staying in one spot, quietly doing their work. But in many situations, cells move, often very quickly. For example, when you get a cut, infection-fighting cells rally to the site, ready to gobble up bacterial intruders. Then, platelet cells along with proteins from blood gather and form a clot to stop any bleeding. And finally, skin cells surrounding the wound lay down scaffolding before gliding across the cut to close the wound.

This remarkable organization and timing is evident right from the start. Cells migrate within the embryo as it develops so that body tissues and organs end up in the right places. Harmful cells use movement as well, as when cells move and spread (metastasize) from an original cancer tumor to other parts of the body. Learning how and why cells move could give scientists new ways to guide those cells or turn off or slow down the movement when needed.

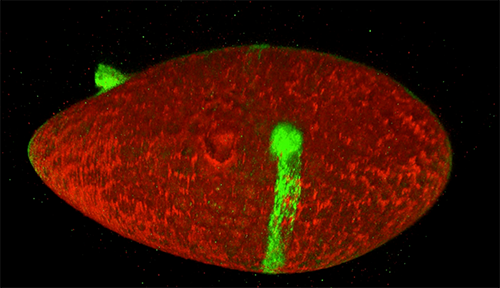

Glowing Breadcrumbs

Scientists studying how humans and animals form, from a single cell at conception to a complex body at birth, are particularly interested in how and when cells move. They use research organisms like the fruit fly, Drosophila, to watch movements by small populations of cells. Still, watching cells migrate inside a living fly is challenging because the tissue is too dense to see individual cell movement. But moving those cells to a dish in the lab might cause them to behave differently than they do inside the fly. To solve this problem, NIGMS-funded researcher David Bilder![]() and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, came up with a way to alter fly cells so they could track how the cells behave without removing them from the fly. They engineered the cells to lay down a glowing track of proteins behind them as they moved, leaving a traceable path through the fly’s tissue. The technique, called M-TRAIL (matrix-labeling technique for real-time and inferred location), allows the researchers to see where a cell travels and how long it takes to get there.

and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, came up with a way to alter fly cells so they could track how the cells behave without removing them from the fly. They engineered the cells to lay down a glowing track of proteins behind them as they moved, leaving a traceable path through the fly’s tissue. The technique, called M-TRAIL (matrix-labeling technique for real-time and inferred location), allows the researchers to see where a cell travels and how long it takes to get there.

Bilder and his team first used M-TRAIL in flies to confirm the results of past studies of Drosophila ovaries in the lab using other imaging techniques. In addition, they found that M-TRAIL could be used to study a variety of cell types. The new technique also could allow a cell’s movement to be tracked over a longer period than other imaging techniques, which become toxic to cells in just a few hours. This is important, because cells often migrate for days to reach their final destinations.

Continue reading “Cellular Footprints: Tracing How Cells Move”

Interview With a Scientist: Joel Kralj, Electromicist

Every one of our thoughts, emotions, sensations, and movements arise from changes in the flow of electricity in the brain. Disruptions to the normal flow of electricity within and between cells is a hallmark of many diseases, especially neurological and cardiac diseases.

The source of electricity within nerve cells (i.e., neurons) is the separation of charge, referred to as voltage, across neuronal membranes. In the past, scientists weren’t able to identify all the molecules that control neuronal voltage. They simply lacked the tools. Now, University of Colorado biologist Joel Kralj ![]() has developed a way to overcome this hurdle. His new technique—combining automated imaging tools and genetic manipulation of cells—is designed to measure the electrical contribution of every protein coded by every gene in the human genome. Kralj believes this technology will usher in a new field of “electromics” that will be of enormous benefit to both scientists studying biological processes and clinicians attempting to treat disease.

has developed a way to overcome this hurdle. His new technique—combining automated imaging tools and genetic manipulation of cells—is designed to measure the electrical contribution of every protein coded by every gene in the human genome. Kralj believes this technology will usher in a new field of “electromics” that will be of enormous benefit to both scientists studying biological processes and clinicians attempting to treat disease.

In 2017, Kralj won a New Innovator Award from the National Institutes of Health for his work on studying voltage in neurons. He is using the grant money to develop a new type of microscope that will be capable of measuring neuronal voltage from hundreds of cells simultaneously. He and his research team will then attempt to identify the genes that encode any of the 20,000 proteins in the human body that are involved in electrical signaling. This laborious process will involve collecting hundreds of nerve cells, genetically removing a single protein from each cell, and using the new microscope to see what happens. If the voltage within a cell is changed in any way when a specific protein is removed, the researchers can conclude that the protein is essential to electrical signaling.

In this video, Kralj discusses how he plans to use his electromics platform to study electricity-generating cells throughout the body, as well as in bacterial cells (see our companion blog post “Feeling Out Bacteria’s Sense of Touch” featuring Kralj’s research for more details).

Dr. Kralj’s work is funded in part by the NIH under grant 1DP2GM123458-01.

Feeling Out Bacteria’s Sense of Touch

Our sense of touch provides us with bits of information about our surroundings that inform the decisions we make. When we touch something, our nervous system transmits signals through nerve endings that feed information to our brain. This enables us to sense the stimulus and take the appropriate action, like drawing back quickly when we touch a hot stovetop.

Bacteria are single cells and lack a nervous system. But like us, they rely on their “sense” of touch to make decisions—or at least change their behavior. For example, bacteria’s sense of touch is believed to trigger the cells to form colonies, called biofilms, on surfaces they make contact with. Bacteria may form biofilms as a way to defend themselves, share limited nutrients, or simply to prevent being washed away in a flowing liquid.

Humans can be harmed by biofilms because these colonies serve as a reservoir of disease-causing cells that are responsible for high rates of human infection. Biofilms can protect at least some cells from being affected by antibiotics. The surviving reservoir of bacteria then have more time to evolve resistance to antibiotics.

At the same time, some biofilms can be valuable; for example, they help to break down waste in water treatment plants and to drive electrical current as part of microbial fuel cells.

Until recently, scientists thought that bacteria formed biofilms and caused infections in response to chemical signals they received from their environments. But research in 2014 showed that the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa could infect a variety of living tissues—from plants to many kinds of animals—simply by making contact with them. In the past year, multiple groups of investigators have learned more about how bacteria sense that they have touched a surface and how that sense translates to changes in their behavior. This understanding could lead to new ways of preventing infections or harmful biofilm formation.

Making Contact

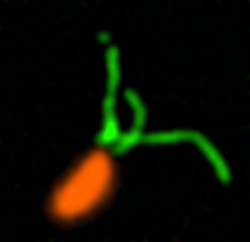

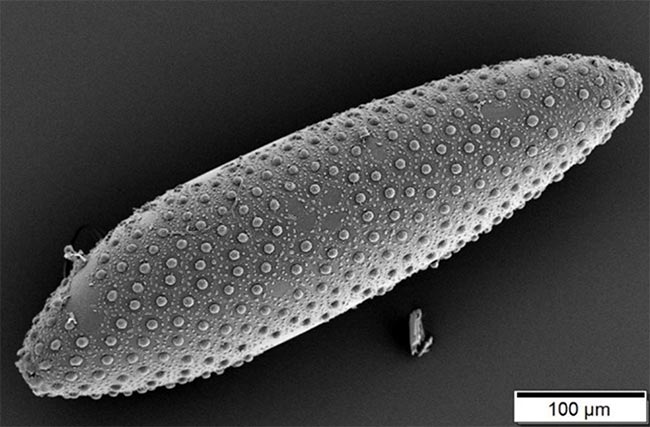

Pili (green) on cells from the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus (orange). Scientists used a fluorescent dye to stain pili so they could watch the structures extend and retract. Credit: Courtney Ellison, Indiana University.

When they first make contact with a surface, bacteria change from free-ranging, swimming cells to stationary ones that secrete a sticky substance, tethering them in one place. To form a biofilm, they begin replicating, creating an organized mass stable enough to resist shaking and to repel potential invaders (see https://biobeat.nigms.nih.gov/2017/01/cool-image-inside-a-biofilm-build-up/).

How do swimming bacteria sense that they have found a potential surface to colonize? Working with the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus, Indiana University Ph.D. student Courtney Ellison and her colleagues, under the direction of professor of biology and NIGMS grantee Yves Brun, recently showed that hair-like structures on the cell’s surface, called pili, play a role here. The researchers found that as a bacterial cell swims in a fluid, its pili are constantly stretching out and retracting. When the cell makes contact with a surface, the pili stop moving, start producing a sticky substance and use it to hold onto the surface. Continue reading “Feeling Out Bacteria’s Sense of Touch”

Viruses: Manufacturing Tycoons?

As inventors and factory owners learned during the Industrial Revolution, the best way to manufacture a lot of products is with an assembly line that follows a set of precisely organized steps employing many copies of identical and interchangeable parts. Some viruses are among life’s original mass producers: They use sophisticated organization principles to turn bacterial cells into virus particle factories.

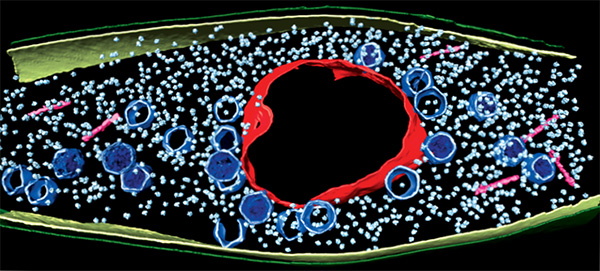

Scientists at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of California, San Francisco, used cutting-edge techniques to watch a bacteria-infecting virus (bacteriophage) set up its particle-making factory inside a host cell.

The image above shows this happening inside a Pseudomonas chlororaphis, a soil-borne bacterium that protects plants against fungal pathogens. The virus builds a compartment (red, rough circle surrounding the center) that helps organize an assembly line for making copies of itself. The compartment looks like a cell nucleus, which bacteria do not have, and it functions like a nucleus by keeping activities that directly involve DNA separate from other cellular functions. Continue reading “Viruses: Manufacturing Tycoons?”

Flipping the Switch on Controlling Disease-Carrying Insects

Suppressing insects that spread disease is an essential public health effort, and scientists are testing a possible new tool to use in this challenging arena. They’re harnessing a microbe capable of controlling insects’ reproductive processes.

The microbes, called Wolbachia, live inside the cells of about two-thirds of insect species worldwide, and they can manipulate the host’s reproductive cells in ways that boost their own survival. Scientists think they can use Wolbachia’s methods to reduce populations of insects that spread disease among humans.

A Switch to Control Fertility

Wolbachia have evolved complex ways to control insect reproduction so as to infect increasing numbers of an insect species—such as those prolific disease-spreaders, mosquitos. One method Wolbachia uses is called cytoplasmic incompatibility, or CI. The end result of CI, basically, is that the sperm of infected male insects cause sterility in uninfected females.

Wolbachia that have infected male insects can insert proteins that produce a kind of infertility switch into the host’s sperm. When the sperm later fuses with an egg from an uninfected female, the switch is triggered and renders the egg sterile. If the female is already infected, her eggs will contain Wolbachia, which can turn off the switch and allow the egg to develop. This trick ensures that more Wolbachia-infected insects will survive and continue to reproduce, while uninfected ones will be less successful.

Already, some states ![]() and countries

and countries ![]() are releasing Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes into wild mosquito populations that carry disease-causing viruses to test this strategy for insect control. Males carrying a Wolbachia strain that strongly induces infertility in uninfected females should reduce the numbers of mosquito eggs that mature, leading to fewer mosquitos. Continue reading “Flipping the Switch on Controlling Disease-Carrying Insects”

are releasing Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes into wild mosquito populations that carry disease-causing viruses to test this strategy for insect control. Males carrying a Wolbachia strain that strongly induces infertility in uninfected females should reduce the numbers of mosquito eggs that mature, leading to fewer mosquitos. Continue reading “Flipping the Switch on Controlling Disease-Carrying Insects”

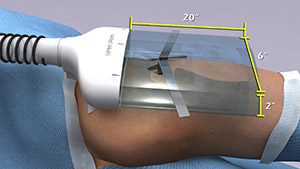

New Technology May Help Reduce Serious and Costly Post-Surgical Infections—Using Nothing but Air

According to a recent estimate, implant infections following hip and knee replacement surgeries in the U.S. may number 65,000 by 2020, with the associated healthcare costs exceeding $1 billion. A new small, high-tech device could have a significant impact on improving health outcomes and reducing cost for these types of surgeries. The device, Air Barrier System (ABS), attaches on top of the surgical drape and gently emits HEPA-filtered air over the incision site. By creating a “cocoon” of clean air, the device prevents airborne particles—including the bacteria that can cause healthcare-associated infections—from entering the wound.

Scientists recently analyzed the effectiveness of the ABS device in a clinical study—funded by NIGMS—involving nearly 300 patients. Each patient needed an implant, such as an artificial hip, a blood vessel graft in the leg or a titanium plate in the spine. Because implant operations involve inserting foreign materials permanently into the body, they present an even higher risk of infection than many other surgeries, and implant infections can cause life-long problems.

The researchers focused on one of the most common causes of implant infections—the air in the operating room. Although operating rooms are much cleaner than almost any other non-hospital setting, it’s nearly impossible to sterilize the entire room. Instead, the scientists focused on reducing contaminants directly over the surgical site. They theorized that if the air around the wound was cleaner, the number of implant infections might go down. Continue reading “New Technology May Help Reduce Serious and Costly Post-Surgical Infections—Using Nothing but Air”

Bit by the Research Bug: Priscilla’s Growth as a Scientist

This is the third post in a new series highlighting NIGMS’ efforts toward developing a robust, diverse and well-trained scientific workforce.

Credit: Christa Reynolds.

Academic Institution: The University of Texas at El Paso

Major: Microbiology

Minors: Sociology and Biomedical Engineering

Mentor: Charles Spencer

Favorite Book: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot

Favorite Food: Tacos

Favorite music: Pop

Hobbies: Reading and drinking coffee

It’s not every day that you’ll hear someone say, “I learned more about parasites, and I thought, ‘This is so cool!’” But it’s also not every day that you’ll meet an undergraduate researcher like 21-year-old Priscilla Del Valle.

BUILD and the Diversity Program Consortium

The Diversity Program Consortium (DPC) aims to enhance diversity in the biomedical research workforce through improved recruitment, training and mentoring nationwide. It comprises three integrated programs—Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD), which implements activities at student, faculty and institutional levels; the National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN), which provides mentoring and career development opportunities for scientists at all levels; and the Coordination and Evaluation Center (CEC), which is responsible for evaluating and coordinating DPC activities.

Ten undergraduate institutions across the United States have received BUILD grants, and together, they serve a diverse population. Each BUILD site has developed a unique program intended to engage and prepare students for success in the biomedical sciences and maximize opportunities for research training and faculty development. BUILD programs include everything from curricular redesign, lab renovations, faculty training and research grants, to student career development, mentoring and research-intensive summer programs.

Del Valle’s interest in studying infectious diseases and parasites is motivating her to pursue an M.D./Ph.D. focusing on immunology and pathogenic microorganisms. Currently, Del Valle is a junior at The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP)’s BUILDing SCHOLARS Center. BUILDing SCHOLARS, which stands for “Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity Southwest Consortium of Health-Oriented Education Leaders and Research Scholars,” focuses on providing undergraduate students interested in the biomedical sciences with academic, financial and professional development opportunities. Del Valle is one of the first cohort of students selected to take part in this training opportunity.

BUILD scholars receive individual support through this training model, and Del Valle says she likes “the way that they [BUILDing SCHOLARS] take care of us and the workshops and opportunities that we have.”

Born in El Paso, Texas, Del Valle moved to Saltillo, Mexico, where she spent most of her childhood. Shortly after graduating from high school, she returned to El Paso to start undergraduate courses at El Paso Community College (EPCC), to pursue an M.D. Del Valle explains that in Mexico, unlike in the United States, careers in medical research are not really emphasized in the student community or in society, so she did not have firsthand experience with research.

Del Valle discovered her passion for research when she was assigned a project on malaria as part of an EPCC course. She was fascinated by the parasite that causes malaria. “It impressed me how something so little could infect a person so harshly,” she says. Continue reading “Bit by the Research Bug: Priscilla’s Growth as a Scientist”

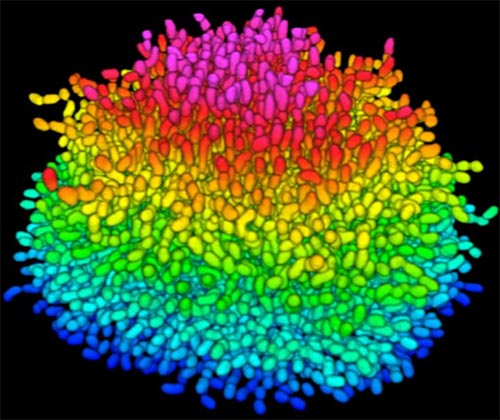

Cool Image: Inside a Biofilm Build-up

Bacteria use many methods to overcome threats in their environment. One of these ways is forming colonies called biofilms on surfaces of objects. Often appearing like the bubble-shaped fortress represented in this image, biofilms enable bacteria to withstand attacks, compete for space and survive fluctuations in nutrient supply. Bacteria aggregated within biofilms inside our bodies, for example, resist antibiotic therapy more effectively than free swimming cells, making infections difficult to treat. On the other hand, biofilms are also useful for making microbial fuel cells and for waste-water treatment. Learning how biofilms work, therefore, could provide essential tools in our ongoing battle against disease-causing agents and in our efforts to harness beneficial bacterial behaviors. Researchers are now using new imaging techniques to watch how biofilms grow, cell by cell, and to identify more effective ways of disrupting or fostering them.

Until now, poor imaging resolution meant that scientists could not see what individual bacteria in the films are up to as the biofilms grow. The issue is that bacteria are tiny, making imaging each cell, as well as the ability to distinguish each cell in the biofilm community, problematic. Continue reading “Cool Image: Inside a Biofilm Build-up”