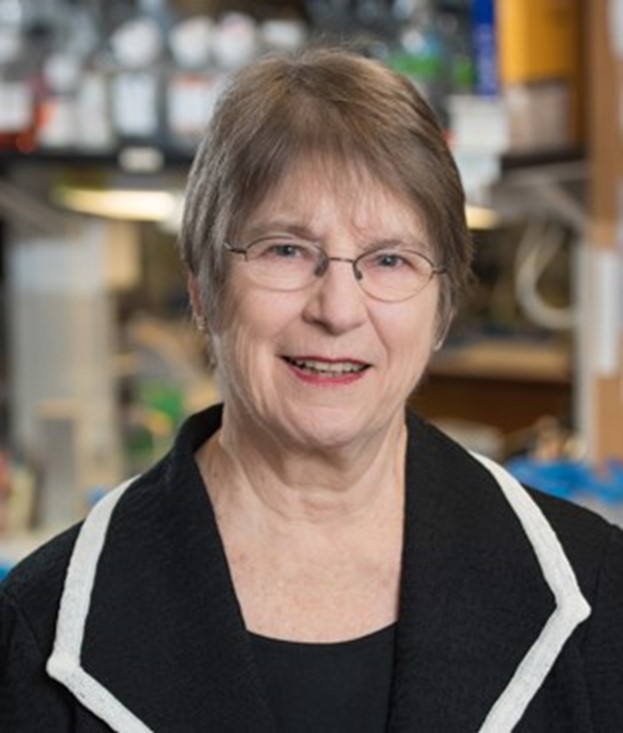

“In my lab, we’ve been gene hunters—starting with visible phenotypes, or characteristics, and searching for the responsible genes,” says Miriam Meisler, Ph.D., the Myron Levine Distinguished University Professor at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor. During her career, Dr. Meisler has identified the functions of multiple genes and has shown how genetic variants, or mutations, can impact human health.

Becoming a Scientist

Dr. Meisler had a strong interest in science as a child, which she credits to “growing up at the time of Sputnik” and receiving encouragement from her father and excellent science teachers in high school and college. However, when she started her undergraduate studies at Antioch College in Yellow Spring, Ohio, she decided to explore the humanities and social sciences. After 2 years of sociology and anthropology classes, she returned to biomedical science and, at a student swap, symbolically traded her dictionary for a slide rule—a mechanical device used to do calculations that was eventually replaced by the electric calculator.

Continue reading “Hunting Disease-Causing Genetic Variants”

A fruit fly expressing GFP. Credit: Jay Hirsh, University of Virginia.

A fruit fly expressing GFP. Credit: Jay Hirsh, University of Virginia.

Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D. Credit: University of California, Berkeley.

Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D. Credit: University of California, Berkeley.

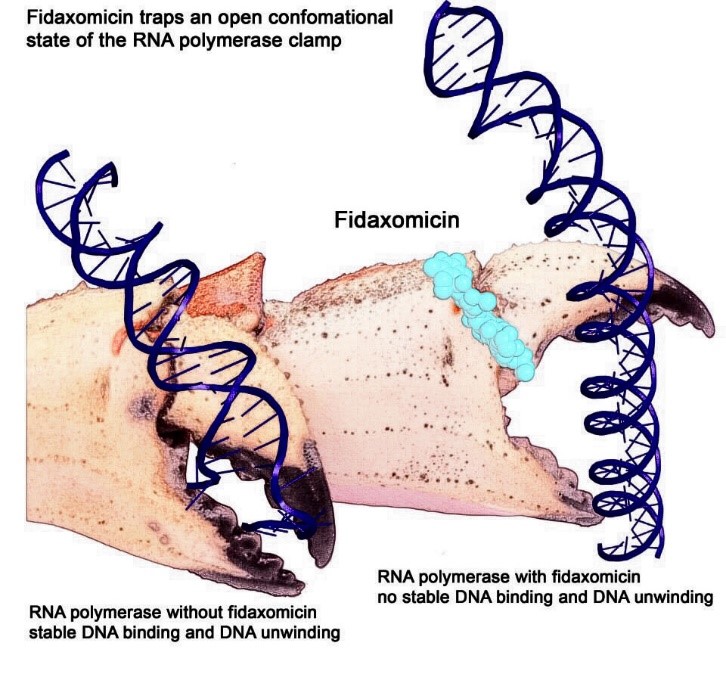

Artist interpretation of RNAP grasping and unwinding a DNA double helix. Credit: Wei Lin and Richard H. Ebright.

Artist interpretation of RNAP grasping and unwinding a DNA double helix. Credit: Wei Lin and Richard H. Ebright.