Here are some images from our gallery that remind us of the winter holidays—and showcase important findings and innovations in biomedical research.

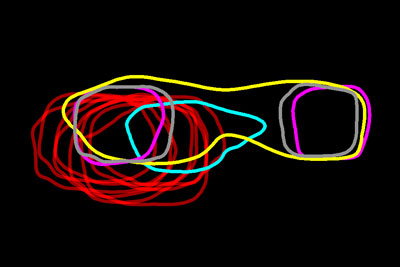

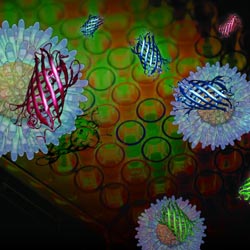

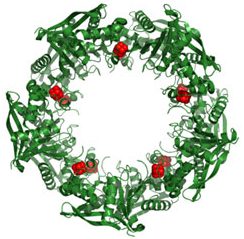

Ribbons and Wreaths

This wreath represents the molecular structure of a protein, Cas4, which is part of a system, known as CRISPR, that bacteria use to protect themselves against viral invaders. The green ribbons show the protein’s structure, and the red balls show the location of iron and sulfur molecules important for the protein’s function. Scientists have harnessed Cas9, a different protein in the bacterial CRISPR system, to create a gene-editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9. Using this tool, researchers can study a range of cellular processes and human diseases more easily, cheaply and precisely. Last week, Science magazine recognized the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool as the “breakthrough of the year.”