This month, our blog that highlights NIGMS-funded research turns four years old! For each candle, we thought we’d illuminate an aspect of the blog to offer you, our reader, an insider’s view.

This month, our blog that highlights NIGMS-funded research turns four years old! For each candle, we thought we’d illuminate an aspect of the blog to offer you, our reader, an insider’s view.

Who are we?

Over the years, the editorial team has included onsite science writers, office interns, staff scientists and guest authors from universities. Kathryn, who’s a regular contributor, writes entirely from her home office. Chris, who has a Ph.D. in neuroscience and now manages the blog, used to do research in a lab. Alisa has worked in NIGMS’ Bethesda-based office the longest: 22 years! She and I remember when we first launched Biomedical Beat as an e-newsletter in 2005. You can read more about each of the writers on the contributors page and if you know someone who’s considering a career in science communications, tell them to drop us a line.

How do we come up with the stories?

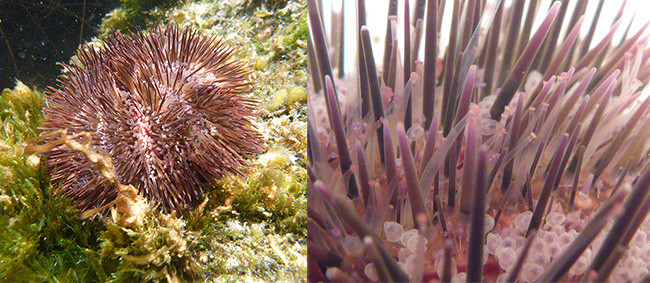

We get our story ideas from a range of sources. For instance, newspaper articles about an experimental pest control strategy in Florida and California prompted us to write about NIGMS-funded studies exploring the basic science of the technique. A beautiful visual from a grantee’s institution inspired a short post on tissue regeneration research. And an ongoing conversation with NIGMS scientific staff about the important role of research organisms in biological studies sparked the idea for a playful profile of one such science superstar.

A big change in our storytelling has been shifting the focus from a single finding to broader progress in a lab or field. So instead of reporting on a study just published in a scientific journal, we may write about the scientist’s career path or showcase a collection of recent findings in that particular field. These approaches help us demonstrate that scientific understanding usually progresses through the slow and steady work undertaken by many labs.

What are our favorite posts?

I polled the writers on posts they liked, and the list is really long! Here are the top picks.

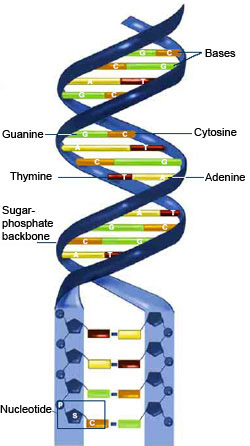

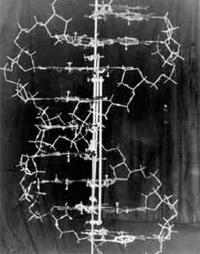

Four Ways Inheritance Is More Complex Than Mendel Knew

The Endoplasmic Reticulum: Networking in the Cell

Interview With a Scientist: Janet Iwasa, Molecular Animator

From Basic Research to Bioelectric Medicine

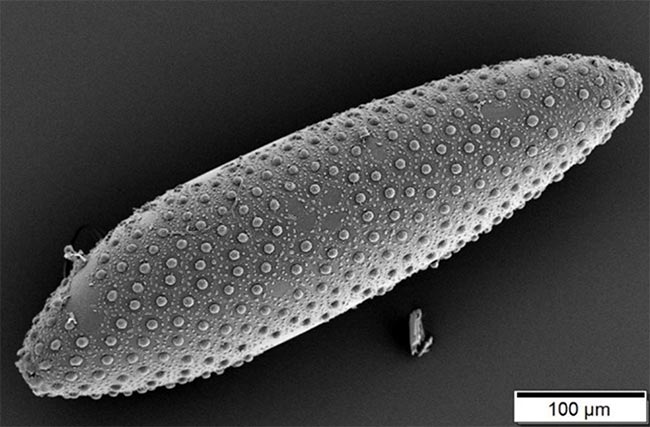

An Insider’s Look at Life: Magnified, an Airport Exhibit of Stunning Microscopy Images

What are your favorite posts?

We regularly review data about the number of times a blog post has been viewed to identify the ones that interest readers the most. That information also helps guide our decisions about other topics to feature on the blog. The Cool Image posts are among the most popular! Below are some other chart-topping posts.

Our Complicated Relationship With Viruses

The Proteasome: The Cells Trash Processor in Action

Demystifying General Anesthetics

Meet Sarkis Mazmanian and the Bacteria That Keep Us Healthy

5 Reasons Biologists Love Math

We always like hearing from readers! If there’s a basic biomedical research topic you’d like us to write about, or if you have feedback on a story or the blog in general, please leave your suggestions in the comment field below.