Sepsis is a serious medical condition caused by an overwhelming immune response to infection. The body’s infection-fighting chemicals trigger widespread inflammation, which can lead to blood clots and leaky blood vessels. As a result, blood flow is impaired, depriving organs of nutrients and oxygen. In severe cases, one or more organs fail. In the worst cases, blood pressure drops, the heart weakens, and the patient spirals toward septic shock. Once this happens, multiple organs—lungs, kidneys, liver—may quickly fail, and the patient can die.

Because sepsis is traditionally hard to diagnose, doctors do not always recognize the condition in its early stages. In the past, it has been unclear how quickly sepsis needs to be diagnosed and treated to provide patients with the best chance of surviving.

Now we may have an answer: A large-scale clinical study, published recently in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that for every hour treatment is delayed, the odds of a patient’s survival are reduced by 4 percent. Christopher Seymour, assistant professor of critical care and emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, and his team analyzed the medical records of nearly 50,000 sepsis patients at 149 clinical centers to determine whether administering the standard sepsis treatment—antibiotics and intravenously administered fluids—sooner would save more lives.

I spoke with Seymour about his experience treating sepsis patients and his research on the condition, including the new study.

CP: How big a public health problem is sepsis?

CS: Our recent work with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests there might be as many as 2 million sepsis cases in the United States each year. I can share personally that sepsis, or septic shock, is far and away the most common life-threatening condition that I treat in the ICU (intensive care unit). It’s quite devastating, particularly among our elders, and it requires prompt care. Although the mortality rate may be decreasing, it’s still quite high. About 1 in 10 patients with sepsis don’t survive their hospital stay. Even young, healthy people can succumb from sepsis. And if you’re fortunate to survive, you can have significant problems with cognitive and physical function for many months to years down the line.

Unfortunately, the incidence of sepsis may even be increasing. More patients are surviving serious illnesses that used to be fatal. They’re alive, but their health is compromised, so they are at higher risk for sepsis. Also—and this is a positive—we are seeing greater recognition and increased reporting of sepsis. Both factors probably contribute to the higher numbers of reported sepsis cases.

CP: What are some of the biggest challenges in fighting sepsis?

CS: The first challenge is public awareness. It’s important that the public knows the word sepsis, that they’re familiar with sepsis being a life-threatening condition that results from an infection, and that they know it can strike anyone—young, old, healthy, or sick. But it’s also important to know that not every infection is septic, nor will every cut or abrasion lead to life-threatening organ dysfunction.

Another part of the problem is that sepsis is not as easy for patients to recognize as, say, myocardial infarction (heart attack). When patients clutch their chest in pain, they intuitively recognize what’s happening. Patients frequently don’t recognize that they’re septic. People should know that when they have an infection or take antibiotics as an outpatient, and they’re starting to feel worse or having other new symptoms, they may be at risk of sepsis. They should go to the emergency department or seek medical help.

The second challenge in fighting sepsis is that it’s just hard to diagnose, even for well-trained clinicians. Both issues can lead to delays in care, the most important of which is the delay in treatment with antibiotics.

CP: Tell me about your recent clinical trial. What question did you set out to answer?

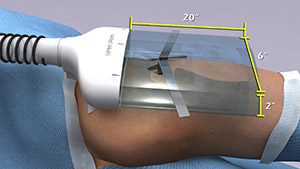

CS: There’s been a lot of interest in the early recognition and treatment of sepsis over the past decade. Recently, the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded a large, multicenter trial called ProCESS, which tested various strategies for treating sepsis. This trial told us that a standardized sepsis protocol among people who had already received antibiotics didn’t necessarily change survival rates. But what it left unanswered was the very important question of when the patient first arrives at the emergency department, how fast do we need to provide antibiotics and fluids for the best possible outcome?

Continue reading “Quicker Sepsis Treatment Saves Lives: Q & A With Sepsis Researcher Christopher Seymour”

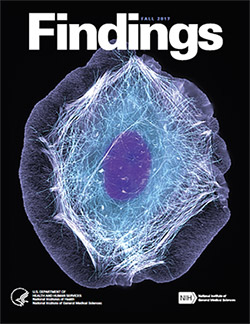

Findings presents cutting-edge research from scientists in diverse biomedical fields. The articles are aimed at high school students with the goal of making science—and the people who do it—interesting and exciting, and to inspire young readers to pursue careers in biomedical research. In addition to putting a face on science, Findings offers activities such as quizzes and crossword puzzles and, in its online version, video interviews with scientists.

Findings presents cutting-edge research from scientists in diverse biomedical fields. The articles are aimed at high school students with the goal of making science—and the people who do it—interesting and exciting, and to inspire young readers to pursue careers in biomedical research. In addition to putting a face on science, Findings offers activities such as quizzes and crossword puzzles and, in its online version, video interviews with scientists. This month, our blog that highlights NIGMS-funded research turns four years old! For each candle, we thought we’d illuminate an aspect of the blog to offer you, our reader, an insider’s view.

This month, our blog that highlights NIGMS-funded research turns four years old! For each candle, we thought we’d illuminate an aspect of the blog to offer you, our reader, an insider’s view.